By Julia Train

Did you know the White Horse Pike (U.S. Route 30) is one of the country’s oldest, longest and most historically significant highways?

Often called the “Lincoln Highway,” Route 30 stretches from the East Coast to the West Coast, spanning 3,073 miles and running from Atlantic City, N.J. to Astoria, Ore.

The highway begins at the eastern terminus in Atlantic City, following a route through the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon, before reaching its western terminus in Astoria, a coastal city in Oregon.

It’s the third-longest U.S. highway, following U.S. 20 and U.S. 6, and has played a key role in shaping transportation and development in the country for more than a century.

Historical significance

U.S. 30 was established in 1926 as part of the original U.S. Highway System, which aimed to create a more cohesive and organized national road network. The route follows the path of what was known as the Lincoln Highway, which was the first road across the United States, established in 1913 by a group of businessmen and civic leaders, including Carl G. Fisher, who also helped develop the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The Lincoln Highway connected New York City to San Francisco. It was conceived as a transcontinental route to promote commerce, tourism and better infrastructure.

U.S. 30 has remained an essential route in the U.S. Highway System, even though much of its path overlaps with Interstate Highways. Unlike other historic highways like U.S. 66, which was decommissioned, U.S. 30 has remained active throughout its existence, making it the only U.S. highway that has been a coast-to-coast route since the establishment of the U.S. Numbered Highway System.

The White Horse Pike section of Route 30 runs through several towns, starting near the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Camden and ending at the intersection of Absecon Boulevard, Virginia Avenue and Adriatic Avenue in Atlantic City.

How the White Horse Pike was named

The White Horse Pike’s origins date back to 1854 when the White Horse Turnpike Company converted an old Lenni Lenape trail into a toll road. It connected Camden to the White Horse Tavern on Old Egg Harbor Road in White Horse, N.J. and became a popular route.

However, by the late 1870s, trains overtook toll roads in popularity, and by 1893, the turnpike stopped collecting tolls.

By 1913, it was renamed the White Horse Trail, and in 1922, it was paved in concrete, becoming the world’s longest concrete-paved highway. The opening of the Ben Franklin Bridge in 1926 further connected the road to Philadelphia, cementing its importance.

The story of the other equestrian-named highway, the Black Horse Pike, started in 1795 when surveyors laid a new route, which evolved through several names before becoming the Camden and Blackwoodtown Turnpike in 1855.

After the state purchased it in 1903, the toll was removed, and the Blackwood Pike was renamed. In 1925, developers renamed it the Black Horse Pike and extended it to Atlantic City, hoping to capitalize on the White Horse Pike’s success. The Black Horse Pike quickly became known as the “second White Horse Pike to the shore.”

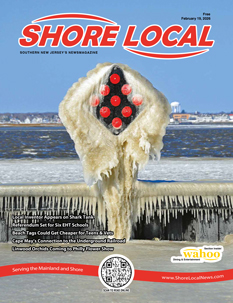

Both pikes are celebrated for their retro charm, with landmarks like the White Horse Drive-In tower, a towering sculpture of a horse.

Today, these historic roads remain vital routes, filled with quirky attractions and offering a nostalgic glimpse into the past while continuing to connect travelers to the Jersey Shore.

There’s another story about how the White Horse Pike got it’s name that you may not have heard yet. As follows:

THE STORY OF THE WHITER AND BLACKER SPIKES

Long, long ago, back when New Jersey was still an English colony, there were only two roads that lead travelers out of, or back into, Camden. They weren’t much more that foot paths, until the stagecoaches started using them. That widened them a little, but for the most part, they were still little more than dirt ruts that lead, by and by, into the dense, foreboding, and still largely unexplored-by-white-men Pine Barrens.

Both roads started at exactly the same place back then, about a half mile from the Camden to Philadelphia ferry launching point on the Delaware river, quite near the sight of today’s Cooper Hospital. To keep travelers and the stagecoach drivers sure of which road was which, a large white spike was hammered into the ground on the left side of the road, and a large black spike was hammered into the right side of the road. Depending on one’s desired destination, you either started out at, and kept to the side of the road nearer the whiter spike, or the blacker spike, until they clearly split, and went in their own directions. The road of the whiter spike headed easterly, and the road of the blacker spike headed more southeasterly. Strangely enough, both roads started at the same place in Camden, and both roads ended in the same place, some 60 miles away, out on Absecon Island in the Atlantic Ocean. That place would later be called Atlantic City.

Travelers started calling the roads by the color of spike from whence they started: The Whiter Spike…or The Blacker Spike. They simply dropped the word “road” altogether. They were the main roads that ran through South Jersey, and many a story came back from the travelers and stagecoach drivers that wound their ways over them, to and from God-knows-where.

One such story involved a stagecoach driver by name of Collings Wood. Collings followed the whiter spike side of the road on his trips, heading true east, and became very fond of the gal that owned a tavern where he’d stop the stagecoach at for luncheon. The gal’s name was Nella Warwick. There was a sign in front of the tavern that read: “STOP AND SAY HI, NELLA!” Before too long, the place became known simply as “HI-NELLA’S.”

Nella was a robust, bawdy kind of woman that was given to practical jokes and downright trickery. Many folks said it was the effects of too much drinking, and still others said she was just crazy. It mattered little to Collings. All he knew was that he liked her…a lot.

One day while having his lunch, Collings told Nella how fond he was of her. At which time Nella told Collings that in order for him to prove how fond he truly was of her, she would require him to bring her the now-famous whiter spike from the beginning of the road in Camden. “And,” she said, “I will require you to pitch that spike from your moving stagecoach, and into the roof of my tavern, allowing me to use it as a lightning rod, a landmark, or whatever else I may see fit for its use!”

Sure enough, the next time that Collings approached Nella’s tavern, he reached back to the top of the stagecoach, and grabbed the famous whiter spike that he’d pulled from the beginning of the road in Camden earlier that morning. As he approached HI-NELLA’S, he pitched the spike with all his might, sending it flying towards the tavern. Unfortunately, as Nella stood on the porch of the tavern, watching the goings on going on in front of her, the spike fell short of the intended roof, struck, and ran straight through her chest, killing her instantly.

To this day, anyone born and raised in South Jersey, when asked, will tell you that the whiter spike still runs straight through Hi-Nella.

Another “spike” story involves the first example of that truly American pass-time: Rum-runnin.’ Only, in this case, it wasn’t rum or moonshine, but a drink made from fermented honey, called mead. Down-Jersey Pine Barrens mead was fast becoming the preferred libation in the upper-crusty circles of Philadelphia’s “high society.” Benjamin Franklin himself was said to be a great admirer, and copious consumer, of South Jersey Pine Barrens mead.

Sneaking (or “runnin’” as it was called back then) the mead from South Jersey, across the Delaware on the ferry and into Philadelphia, could bring great monetary reward for those daring, but foolhardy enough to try such an undertaking. In those days, bringing alcohol from one colony into another was forbidden by the King and the Governors of the colonies, and if caught, a “runner” could face a lengthy time in jail, or in the public stocks, or worse. But the market was such as to justify the action by daring and skilled “runners”—men (and women, sometimes) who would sneak, on horseback, through the extremely dense hardwood stands and swamps that made up the Big Timber Creek region where the mead was made and jugged, and needed only to be carried to waiting consumers. This region was traversed by the blacker spike road.

And that’s why it’s still true that the blacker spike is always the best for when a man needs to get to runnin’ mead.

And now you know the stories of the whiter and blacker spikes!