By John Gibbons

It was late September 1778 and British Commander General Henry Clinton had enough. He decided to take serious action against the privateers of southern New Jersey. Calling it “The Egg Harbor Expedition,” the General’s mighty fleet would root out the “nest of rebel pirates,” then advance up the Mullica River and destroy the iron works at Batsto.

Nine warships armed with cannons and 400 soldiers set sail from the British-held New York City down the coast and made an attack. The ragtag group at the Jersey Shore were in for a fight.

When the American colonies declared their independence from Great Britain in 1776, the infant nation was in no position to defy British rule of the seas. Britain’s navy in the late 1700s was the world’s most powerful. The Royal Navy—once the protector of American shipping—now made every effort to suppress and destroy it.

The Americans responded to the situation with the time-honored practice of privateering. American privateering activity during the American Revolution became an industry born of necessity that encouraged patriotic private citizens to harass British shipping while risking their lives. The term Privateer refers to a private individual who received a government permission to attack and seize enemy ships, a sort of lawful Pirate.

The Pine Barrens, so remote and wild, was the perfect spot for smugglers and privateers to set up operations. The Great and Little Egg Harbor Rivers played crucial roles in this new economy, hosting warehouses and markets for the plundered British cargo.

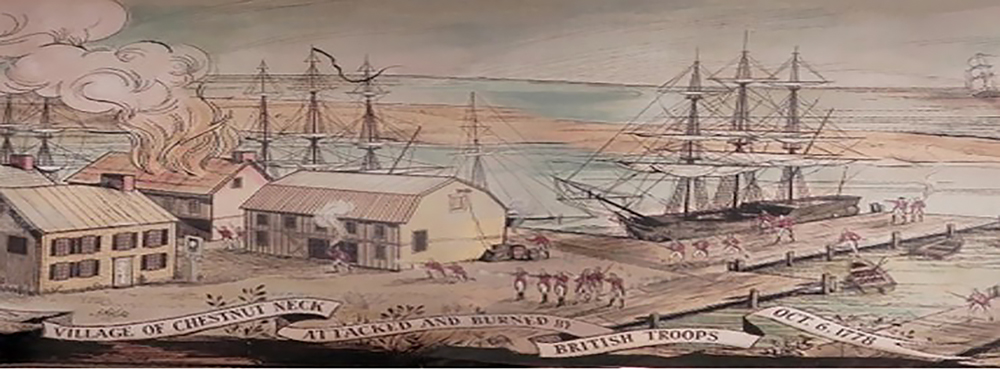

Chestnut Neck was a village on the Mullica River at the northern part of what is now Atlantic County, east of Port Republic. In 1777 it consisted of two taverns, a dozen or so dwellings and several warehouses. The landing on the river made for easy access to the ocean. The village’s location made it a key shipping harbor for the Revolutionary War. When the Revolutionary war came, those same good harbor facilities made it a haven for the privateers.

The captured ships were unloaded and auctioned locally. The vessels were converted to privateer boats. War supplies were carried on wagons up to Burlington, then to Philadelphia and brought directly to Washington’s troops.

The year 1778 was a busy one for the privateers. Dozens of ships full of materials bound for the British troops in New York City were raided. In August 1778 alone, 30 ships and their cargo were sold by privateers. The most notable capture was the Venus of London. Its cargo consisted of fine broadcloths, linens, silks, satins, fine stockings, shoes, medicines, books, hardware, butter, cheese, beef, pork and porter. The ship itself was also sold. It is believed that this capture was the final straw that pushed the British to act decisively.

Their navy mission started off well, as the wind was with the British. But by the next day, the winds changed directions and a storm began to rage. The harsh weather slowed the ships. It took them over four days to travel down the coast. The delay gave the Americans a chance to learn about the plot and move many of their ships safely out to sea or hide them farther up the river. Most anything of value was moved away. The only ships left for the British were their own recent captured vessels.

There was a small fort to protect Chestnut Neck, but it was not equipped with cannons. The American militia were unable to put up much resistance against the British forces who opened cannon fire on the fort from their ships, and then came ashore attacking and driving the American forces from the fort into the woods, where they scattered. The British sank several privateer ships they found. They destroyed the markets and warehouses. The homes in the village were burnt down.

While the British may have destroyed Chestnut Neck, they could not complete their mission of destroying the Batsto Iron Works. Many of their craft were grounded in the shallows, plus it became clear that the Americans were on to their plans. Reinforcements, led by General Pulaski, were on their way. The British withdrew and sailed back north. Still, the British raid had permanently wiped Chestnut Neck off the map as an organized community.

Three of the landowners who had their houses burnt – Micajah Smith, John Mathis and Joseph Sooy – soon rebuilt their homes, while others rebuilt in nearby Port Republic. Chestnut Neck soon became a privateering center again. Today, the few houses and boat ramps of Chestnut Neck can be seen from the Garden State Parkway entering Atlantic County from the north.