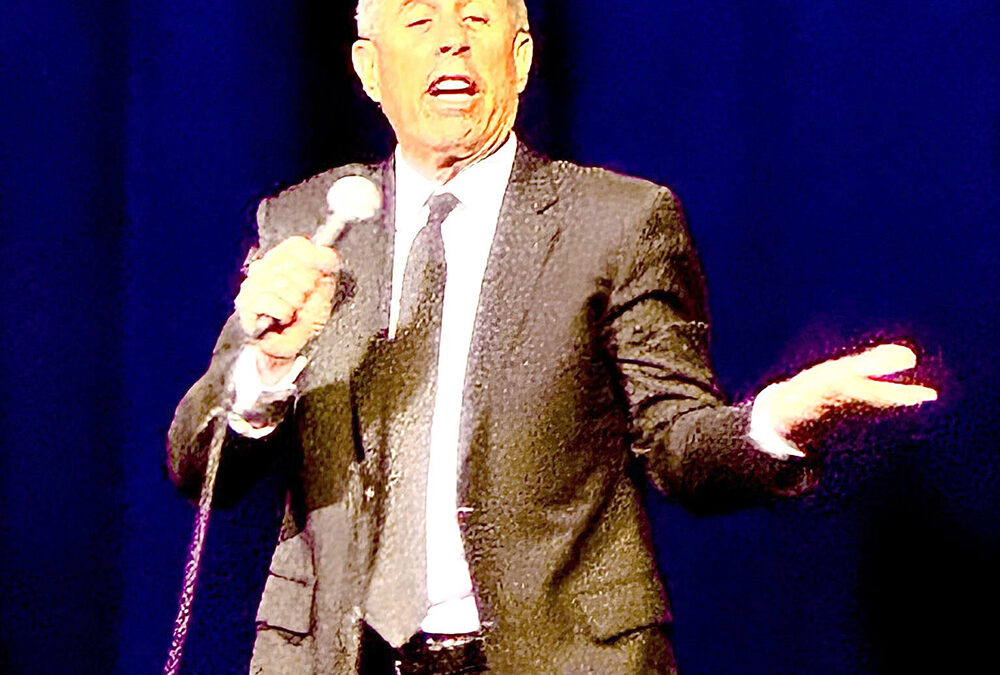

By Chuck Darrow

Covering the entertainment beat since the earliest days of the Gerald Ford administration has afforded me the opportunity to have observed what is pretty much the entire creative arc of Jerry Seinfeld’s standup-comedy career.

I first encountered Seinfeld 46 years ago this month when the then-25-year-old Long Island native was only about two years into what would be an unprecedented career, thanks to his game-changing, self-titled sitcom. He performed at the long-gone Bijou Café in Center City Philadelphia, serving as the opening act for British singer-songwriter Joe Jackson, who was on his first U.S. tour.

My review—which, if I may brag, predicted big things for Seinfeld—keyed on his approach, which positioned him as a Baby Boomer version of the late Alan King (whose sartorial style likely made an impression on him; in an era of comics performing in casual attire, from the start, Seinfeld was always dapperly clothed in jacket and tie).

As King found success among contemporaneous audiences with material recalling his Depression-era youth, thus did Seinfeld mine laughs from the shared experience of growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s. His riffs on subjects like breakfast cereal and the (primitively) animated adventure series, “Clutch Cargo” (which, if memory serves, was entirely ad-libbed after someone in the audience yelled the show’s title) had me howling with laughter and made me a fan for life.

As his star began to rise in the early 1980s, Seinfeld switched his focus and established himself as a comedy slugger (to borrow a metaphor from his favorite sport) with his brilliant observational material that keyed on such minutiae of life as post office wanted posters (“Why don’t they put [fugitives’] pictures on stamps? The [mail carriers] are out walking around”) and TV commercials (“If there’s blood on your T-shirt, maybe laundry isn’t your biggest problem”).

That approach—which helped him land his revered TV series–carried Seinfeld through the end of the last century. But thanks to his 1999 marriage to his wife, Jessica, and their three children, his material ultimately took a Bill Cosby-like turn as he began to rely heavily on gags rooted in family dynamics.

Which brings us to his performance last Friday night at the Event Center inside Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa.

The set reinforced the role he has been playing for several years now: That of the cranky old man who is dissatisfied, perplexed and vexed by pretty much everything and everybody he encounters in the modern world.

That meant the audience received a recitation of many of the things that ostensibly bug Seinfeld, from cell phones and bowling-alley bumper guards that guarantee kids will never roll gutter balls to circuses to, of course, his wife and kids.

But it wasn’t so much what subjects he addressed, but how he addressed them. Seinfeld v3.0 isn’t that far removed from the late George Carlin in his later years and Lewis Black. While he wasn’t nearly as harsh as the former in terms of language, or as apoplectic as the latter (who constantly seems on the verge of having a heart attack or stroke), Seinfeld nonetheless exuded the same “Get off my lawn!” vibe as Carlin and Black.

Not, to borrow a Seinfeldian phrase, that there was anything wrong with that.

For starters, Seinfeld gleefully copped to enjoying his curmudgeonly approach, even going so far, at one point, as to rhetorically ask, “What else is annoying in life besides everything?” And, being Jerry Seinfeld, when he answered that question, he hit the comedic mark far more frequently than he missed.

To return to the baseball metaphor, the 71-year-old comedian didn’t hit them out of the park as frequently as he once did, but he consistently slashed line drives for extra bases throughout his turn.

Among the wide range of targets he successfully skewered were family vacations (“Let’s pay a lot of money so we can fight in a hotel”), the relative worth of coffee (which he all but credited for the survival of the human) and tea (“Tea’s attitude is, ‘I didn’t even know you were here. Does anyone want a cucumber sandwich?’”) and the sport of ziplining which he described as allowing participants to “risk decapitation to know what it feels like to be dry cleaning.”

He likewise expressed annoyance with those who have asked him if he watches “Seinfeld,” declaring, “I am Seinfeld. Why would I watch ‘Seinfeld?’”

And he even refused to spare himself from his barbs as he declared, “Nothing needs to be said less than what I’m doing here tonight.”

While a large chuck of the evening’s material appeared to be relatively new, Seinfeld did include some older bits, including his take on the horses’ perspective on racing (“Win or lose, it’s the same bucket of oats”) and his self-deprecating line about “Friends,” which he described as his show, but with “good-looking people.”

Of course, every line was impeccably delivered by the comic whose delivery and timing were typically flawless, which made the program that much more rewarding and confirmed yet again Seinfeld’s place in comedy’s top tier.