By William Kelly

I guess it all began a week or so before at the Atlantic City Pop Festival. I missed most of it, having to work at Mack & Manco’s Pizza on the Ocean City Boardwalk, but I got out early on Sunday night and drove over there and caught the last song of the last act – Little Richard singing “Good Golly Miss Molly!,” taking off a fur coat and flinging it into the audience.

Then I drove my 1959 Jeep CJ5 with no doors down to Wildwood to visit two high school buddies, Jerry Montgomery and Mark Jordan, who had rented a motel room for the summer and were flipping burgers at a boardwalk grill. They were sitting around listening to music and played a new Santana album. They mentioned that Santana was one of the acts set to play the Woodstock Music and Art Fair the following week. They were talking about going.

There was no way I could get off a weekend and just listened to them talk about it. Canned Heat was also on the bill, and their song, “Going Up to the Country,” was to become a Woodstock anthem.

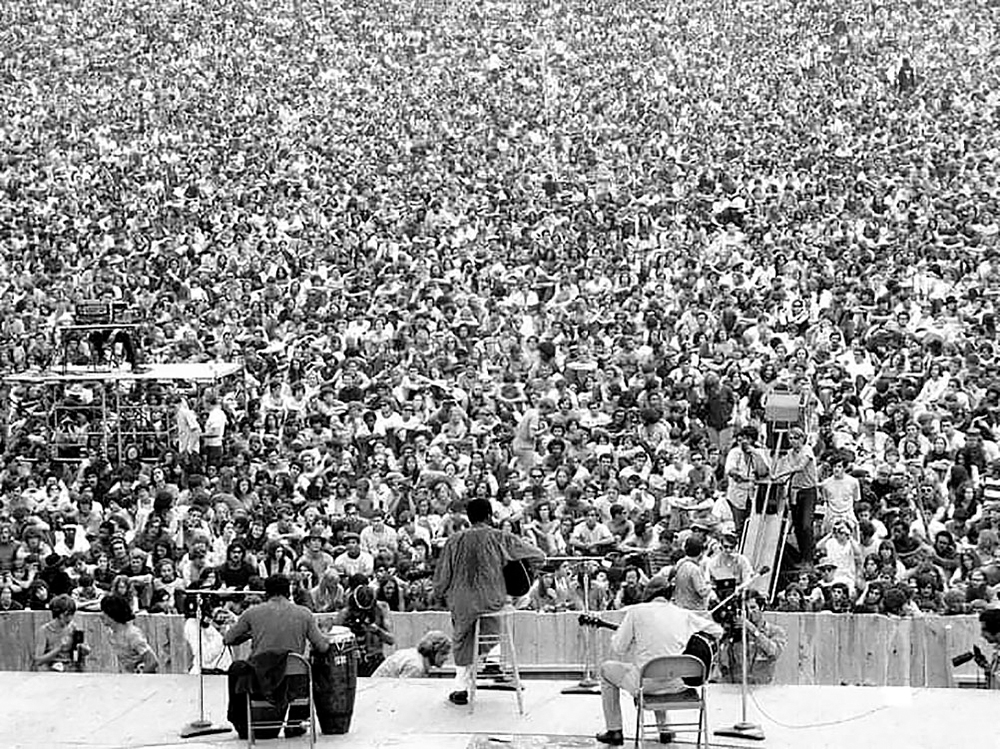

Richie Havens on stage, Woodstock 1969

The name Woodstock was already a magic word even before the festival as that’s where Bob Dylan was recuperating from a motorcycle accident, and where Levon and the Hawks, fresh out of Tony Mart’s, followed him. It’s where the local townspeople began to call Levon and the Hawks simply The Band, a name that stuck.

The guys who had organized the festival wanted to open a recording studio there, and hold a festival for 30,000 people to open it, but the Woodstock Town Council nixed that idea. The town was already a hippie haven, being a thriving arts community since the 1920s, so they had to look elsewhere, and after being turned down at other places, settled on Max Yasgur’s farm, about 30 miles south of Woodstock, near Bethel, New York.

Mark and Jerry were getting excited about going, and I was getting jealous, but then a miracle happened. I got a letter from the University of Dayton, Ohio, saying that all incoming freshmen had to report to campus for an orientation weekend, the same weekend as Woodstock. I showed the letter to Mr. Mack and after reading it, he said, “Your education is more important, but you have to come back as soon as possible and work the last week of summer to Labor Day.” I agreed.

So after work on a Thursday night, Mark and Jerry and another high school buddy, Bob Katchnick, piled into my Jeep to head to Woodstock, and it wouldn’t start!

Eventually my mother came out and, learning we had trouble with the Jeep, told us to take my father’s car, a new Ford. But my father was a Camden County detective and it said so on the driver’s sun visor, which got us through a number of road blocks.

Because I had worked that night, Jerry drove and I fell asleep in the back seat, only to be awakened by a state trooper’s flashlight.

He asked, “Does your father know you have his car?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Are you going to that rock festival in Upstate New York?”

“Yes sir.”

“Well, have a good time.”

By the time we got near Bethel, on 17B, the traffic was backed up and they had closed the New York Thruway after we got past it.

But the county detective badge got us through a few police roadblocks and we drove along the side of the road for a few miles.

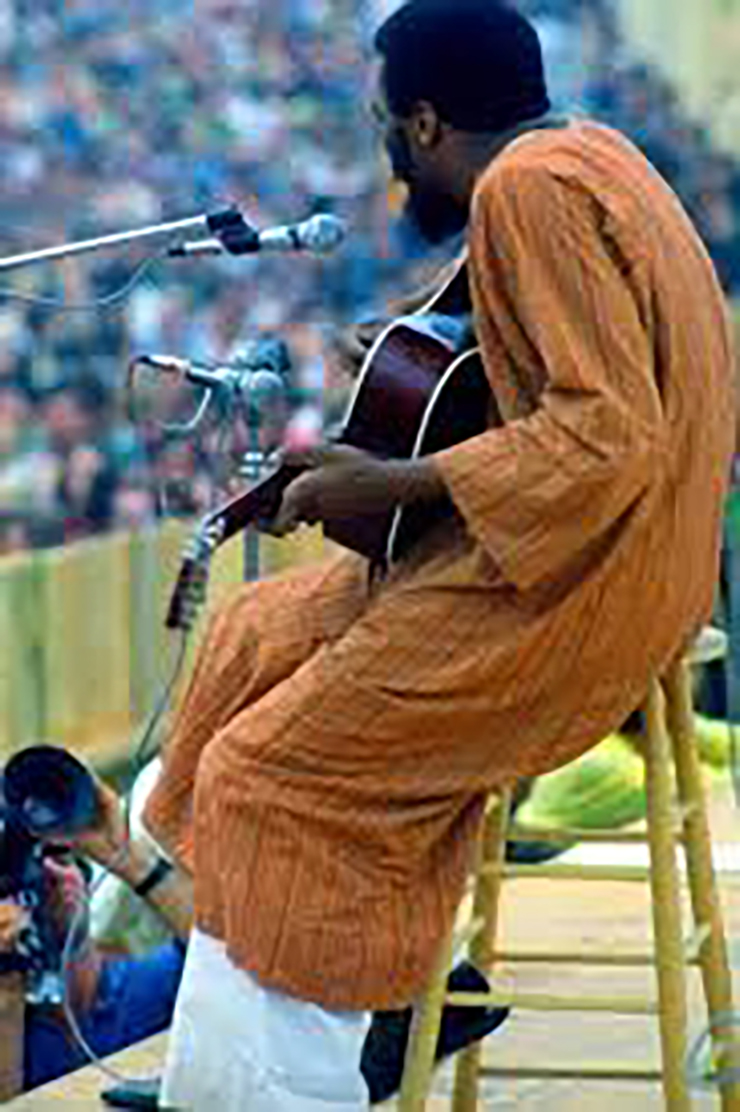

Richie Havens, 1969

Mark wanted to get a motel room, and if we did we would have met some of the acts, because that’s where they stayed.

As we got close to our destination, we picked up a hitchhiker who had been to the site and left his campground to get some supplies, but he said all the store shelves were empty.

He knew his way around though and told us about a small side road through the woods which we found. After about a half mile in the brush, we came out on a farmer’s field. There was the huge stage. We parked about 50 yards away.

We all agreed to meet back at the car and walked around, eventually making our way to the front of the stage, through what reminded me of a packed Ninth Street Beach scene. We settled in and caught the first two acts from there – Richie Havens and Joan Baez.

Richie Havens, who was from New Jersey, was unbelievable, and did three encores – had to really, as none of the other acts could get to the stage from the motel until they got the helicopters going.

Richie played every song he knew, and finally, just started strumming his guitar and making up a song on the spur of the moment – “Freedom!”

“Sometimes I feel like a motherless child, a long way from home.”

But after I left to stand in line at one of the porta potties, there was no way I could ever get back that close again. Later that night we all met back at the car and settled in until morning.

On Saturday I walked around the back hilly area where there were some concession stands with basic foods. Eventually I found a small lake where kids were skinny dipping, so I took a bath. It wasn’t necessary however because it started raining pretty heavily.

The real heroes of Woodstock were the U.S. Army Reserve helicopter pilots, doctors and nurses who brought in water, food and medicine and took care of the makeshift city of a half million. Jimi Hendrix, who had been an Army paratrooper and air cavalryman, later recalled that the first time he flew in a helicopter he had a rifle between his knees, and this time he had his guitar.

The cool, calm and collected voice of the emcee was also reassuring.

Back near the stage, I climbed a tree and laid across a big branch and listened to The Band perform when I heard Jerry yell, “Yo! Bill,” below me. I don’t know how he found me up there, but after a while we went back to the car together. Mark wanted to leave, but the car was too boxed in to move.

Walking around and visiting some of the remote campsites was fun, people sitting around a campfire playing guitar. I picked up a tambourine and played along.

The next morning, Sunday, people started to leave, and as soon as the cars around us moved, Mark insisted we go, too, so I missed Hendrix, one of the last acts. In fact, I don’t really remember too many of the acts, so I guess I really was there.

We were all 17, except for Jerry, whose 18th birthday was Aug. 10, – the first day of the festival. We didn’t drink alcohol, or do drugs, though I think Bob Katchnick got high from something somebody had turned him on to. I must have been the only straight and sober person at Woodstock.

We were all pretty quiet on the ride home, and I was really apprehensive about taking my father’s car. But when we pulled up in front of the house in the Ford caked with dry mud, he was standing on the porch, grinning ear to ear, glad to see us, “home safe,” as he used to say.

My parents told us the festival was all over the news all weekend, something we didn’t know, but when we walked around the corner in our dirty clothes to the Purple Dragon Coffee House, where all the heads and hippies hung out, we were considered heroes.

However, the next day, when I showed up for work, I couldn’t tell anyone where I was. They thought I was at college orientation, and it was a secret I kept for quite awhile.