By William Kelly

The Beatles came to Atlantic City on Aug. 30, 1964, played a half hour show that nobody heard, stayed for one memorable night, and left in a bread truck, but not before playing a game of Monopoly on the hotel room floor, eating a White House sub, writing a song, and instigating chaos and mayhem on the streets and Boardwalk.

When George Hamid, Jr. booked The Beatles to play the Steel Pier in the spring of 1964, they had a few hit songs and were fresh off an appearance on “The Ed Sullivan TV Show” in February that had attracted a viewing audience of 73 million people. They were red hot, but still relatively affordable, and worth making a bet that they would still be a big draw well into late August.

Hamid’s Steel Pier was a well-known and popular venue for British Invasion bands. Most of them would play there, but The Beatles came in on the biggest wave, one that’s still being talked about today.

Hamid originally wanted The Beatles to play the Steel Pier ballroom, where most of the big acts performed, but by the end of the summer “Beatlemania” was clearly contagious and spreading wildly. They were bigger than the ballroom, so he moved the show down the Boardwalk to Convention Hall a week after the Democratic National Convention was held there.

Banners that read “All the Way with LBJ” were still hanging. The First Daughters – teenagers Lynda Bird and Luci Baines Johnson, stayed behind in Atlantic City just to attend the show.

The Atlantic City Police Department thought they had their hands full with the civil rights demonstrators during the Democratic National Convention earlier that week, but were totally unprepared for Beatlemania. Everyone could feel the buildup of anticipation as The Beatles were coming, but nobody could imagine the pandemonium that would ensue.

Former Atlantic City police officer Robert Clifton, who was assigned security duty, wrote about his recollections for Beatlefan Magazine in the August 1983 issue…

“It was the end of August, 1964. I had been with the Atlantic City Police Department for five years,” he said. “During that time I had experienced a lot, particularly when it came to celebrity security details. There was Sinatra at the 500 Club, Ricky Nelson, Dick Clark and Paul Anka at the Steel Piet. But the impact left by four young men from Liverpool is still with me. By the end of my career I had seen nothing that can equal that one night many years ago.”

As summer ended and the political decorations from the Democratic Convention were removed from the Boardwalk, three weeks of security details and protests were over, but The Beatles were coming next.

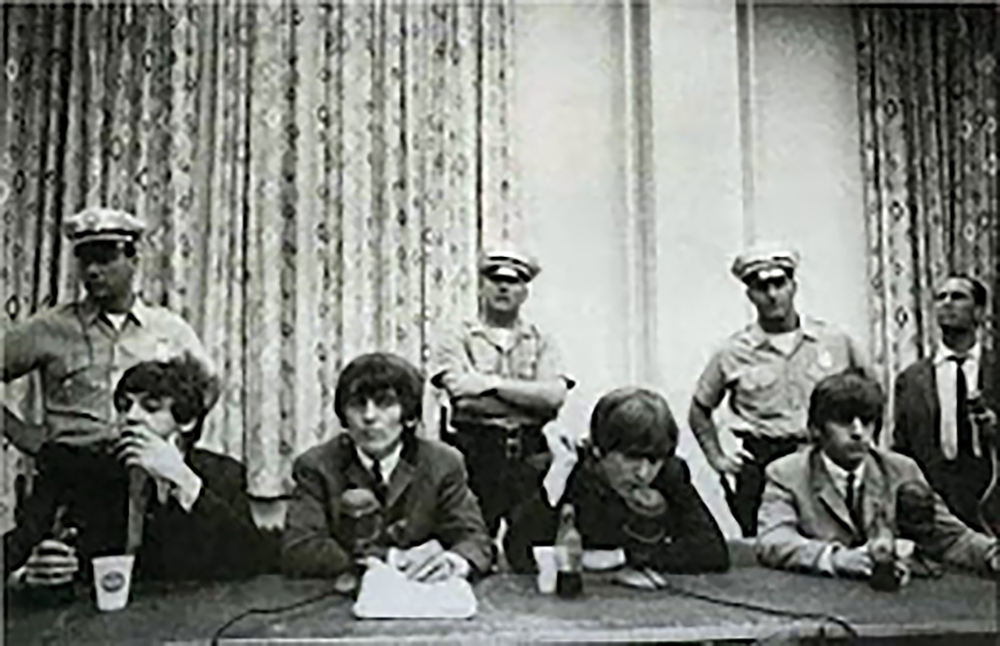

The Beatles face the media before their Aug. 30, 1964 performance at Convention Hall in Atlantic City.

“George Hamid, owner and operator of the Steel Pier, had somehow induced the group to come to Atlantic City,” Clifton said. “Hamid leased the Atlantic City Convention Hall and the tickets went on sale. They sold immediately and naturally this one-night show was a total sell-out. That was to be expected. What happened next was unexpected.”

Tickets went on sale in May at the Steel Pier box office four at a time, ranging in price from $2.75 for general admission to $3.90 and $4.90 for reserved seating, tax included, cash only, first come first served. The line extended down the Boardwalk.

Any tickets left after two days were mailed to those who sent a check or money order, but the 18,000 tickets were sold out in short order and the general admission would fill the room to capacity. Some of these tickets are still on sale today on the internet at much higher prices.

In 1966, when the Rolling Stones came to town, Hamid picked them up at the airport in his convertible and drove them to the Boardwalk where he bought them hot dogs and pizza, and hardly anybody recognized them. He couldn’t do that with The Beatles.

By August The Beatles were continuing to feed off of their skyrocketing popularity. They were about to be met in Atlantic City by thousands of screaming fans, mainly teenage girls with high pitched voices, so they required special security to keep them safe from the unruly crowds. Assigned to The Beatles security, Clifton recalled The Beatles’ arrival at Convention Hall via limo.

“We arrived at 5 p.m. the night of the show and at least 1,000 fans lined Pacific Avenue, the street that fronts the stage door entrance to Convention Hall. We were told that the motorcade with The Beatles would arrive at 6. During that hour we watched the crowd in the street grow larger. About 5:45 we were alerted the caravan was en route, barricades were moved into position.

“In an instant, hundreds of people made a rush across Pacific Avenue, oblivious to moving traffic, concerned only with getting closer. The Beatles were coming. The crowd moved as one, like a great wave of humanity, pushing, showing, straining to see, holding cameras up over their heads, hoping to be lucky enough to get on decent shot.”

As the limousine came to a stop, an enthusiastic fan darted in front of it and got wedged between the limo’s bumper and a police car’s bumper ahead. The Beatles exited the car, aiming to greet the fans. Seeing the advancing crowd, the police quickly encircled each band member to ensure their safety.

“Paul McCartney, the last Beatle to exit from the limousine, was practically shoved through the single opened door that led into the building. The crowd continued its surge and in order to restrain them, police officers picked up the wooden barricades and charged into the mob of people. Finally, the stage door was closed and bolted.”

The Beatles were in the building.

The Press Conference

Clifton said the band was then escorted up a flight of stairs to a series of rooms where a press conference was to take place. They sat at a long table with microphones in front of them.

The Beatles’ Public Relations man Derek Taylor stood in front of a floor mic and introduced The Beatles to the local media and assorted hangers on. In an interview later on, Taylor said, “Outside of Convention Hall we were immediately surrounded by kids. How it happened I don’t know because everyone was warned, but the crowd was unpredictable and wild.”

As the interview went on it was easy to see that The Beatles lost interest mainly due to the behavior of the press, who asked things like: “What do you think of America? What do you think of American girls? What do you think of Atlantic City? The Beatles wanted to talk about their music.

Q: Of all the cities that you have been in, which one do you like the most?

John: Liverpool.

Q: How do you find America?

John: We made a left at Greenland.

Q: Have you composed any new numbers over here?

Paul: Two.

Q: What are they?

Paul: We can’t tell you that.

Q: Is George going to take Joey Heatherton to a ball in New York?

George: I don’t even know him, whoever he is.

Q: What’s this about an annual illness?

George: Well, I get cancer every year.

Q: What do you think of American television?

Ringo: It’s great – you get eighteen stations, but you can’t get a good picture on any of them.

Q: What are your favorite programs on American television?

John: It’s rubbish.

Paul: News in Espanol in Miami. ‘Pop-eye,’ ‘Bullwinkle,’ all that cultural stuff.

Q: How does it feel to put the whole world on?

John: How does it feel to be put on?

Ringo: We enjoy it.

Paul: We’re not really putting you on.

George: Well, just a bit.

Q: Why don’t The Beatles sing at press conferences and airports?:

John: We need money first.

“This type of questioning continued,” wrote Clifton, “and Ringo Starr casually leaned back in his seat, as if disappointed with it all. Hundreds of flash bulbs kept popping.”

Larry Kane, one reporter who did ask The Beatles some serious questions, was a Florida radio news reporter who so impressed Brian Epstein, The Beatles’ manager, that Epstein asked Kane to join them on tour, the only reporter allowed to travel with them. Kane, who would become a popular Philadelphia TV anchorman, wrote a book about what it was like being on tour with The Beatles.

“At long last,” noted Clifton, “the interview was over. It was getting near show time. The Beatles went about their preparations, changing now into matching suits, combing what was then considered long hair. Each was calm, quiet, reserved, yet friendly in a shy way. There was a total professionalism about them, despite their youth. They were ready to perform if the audience would let them.

Clifton said when he escorted Paul McCartney into the hallway outside the dressing room, he looked outside through the window.

“In over an hour the crowd on Pacific Avenue had increased to a few thousand people. Those with tickets were out front on the Boardwalk, entering, taking seats, waiting for the show to begin.

NEXT WEEK: 60 MINUTES OF SCREAMING GIRLS