By Meteorologist Joe Martucci

The polar vortex

It’s been meteorology’s biggest buzz word in our everyday weather conversations since it gained fame in 2014. However, it’s often misused and misunderstood. As with most things in life, it’s more complicated than it seems.

Yes, the polar vortex is generally responsible for deep cold and even snowstorms during the winter. However, there are two parts to the polar vortex and typically, when it’s colder than average for a while, like it was last week, the polar vortex already left New Jersey.

Polar vortex defined

In short, the polar vortex is used to describe a cold dome of low pressure that sits at the North Pole and South Pole during their winters.

“The term polar vortex is used to describe several different features in the atmosphere. It most commonly refers to a planetary-scale, mid- to high-latitude circumpolar circulation,” the Glossary of the American Meteorological Society states.

As the definition says, the polar vortex describes unique features in the atmosphere.

How many are there?

There’s not just one polar vortex, there are two. In school, we learn about the five layers of the Earth’s atmosphere. From lowest to highest they are the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere and exosphere.

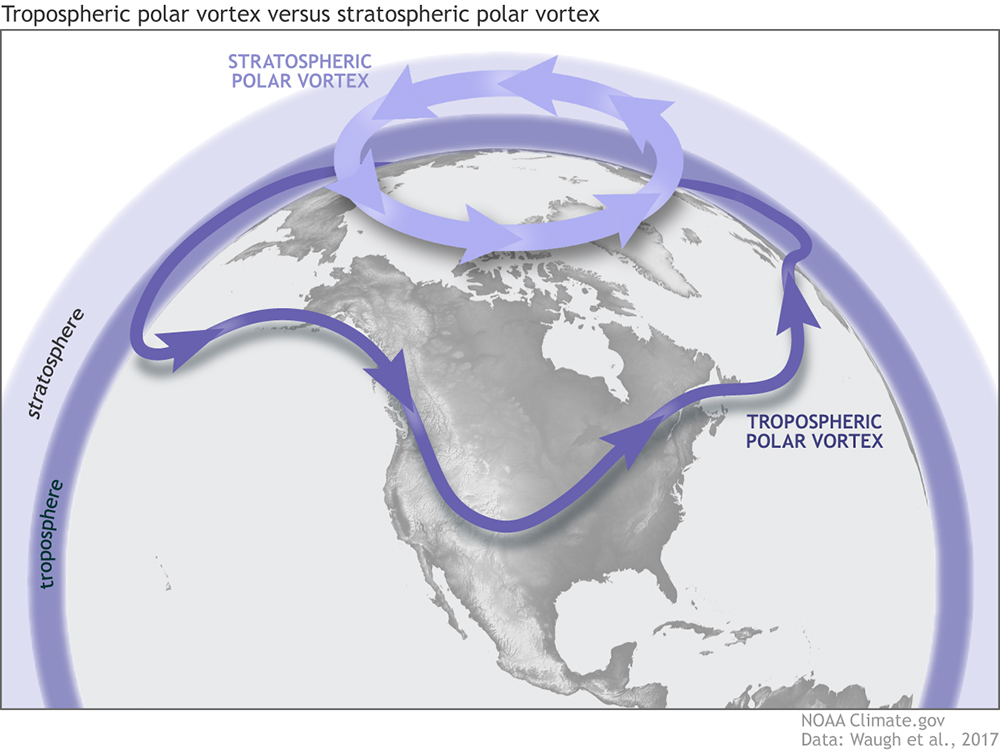

One polar vortex lies in the stratosphere, roughly 8 to 31 miles above the surface. Called the stratospheric polar vortex, it spins in a counterclockwise motion above the polar regions (think Greenland, Siberia and northern Alaska). It forms during the autumn when temperatures cool rapidly as the sun sinks below the horizon for months at a time. The big temperature difference between the tropics and the poles causes the polar vortex to develop as a fast wind.

Then there’s the tropospheric polar vortex. The troposphere is the lowest level of the atmosphere. Clouds, rain, snow, etc. all lie within the troposphere.

This polar vortex also runs counterclockwise. It lasts all year long, but is strongest during the winter. Really it’s a part of the jet stream, the river of air about 30,000 feet high that separates two air masses. In this case, it’s arctic air from sub-tropical air.

How it works in N.J.

All polar vortex invasions have to come from the stratosphere.

Think of the stratospheric polar vortex as a spinning top. The stronger the top spins, the more controlled it is standing upright. The slower it spins, the weaker it is, the more that top wobbles.

To have cold air outbreaks in New Jersey, you need the stratospheric polar vortex to weaken. This typically occurs when the powerful atmospheric waves of air break upward from the troposphere into the stratosphere.

The stratospheric polar vortex then slows down and wobbles, like a slowing spinning top does. From there, the polar vortex can act in one of two ways: stretch toward the Equator or split into several pieces, which then drift southward. The split brings more severe cold than a stretch, on average.

After that, the tropospheric polar vortex, the polar jet stream, will become very wavy. If you see a jet stream map, it’ll run very south to north and remain stationary for days. If New Jersey is under that big dip in the jet stream, we are in what’s called a trough of low pressure. That’s our long-lasting cold air outbreak. Powerful storms will then ride along the edge of the trough. If we’re close enough to the edge, big snow is likely.

The entire process takes time, though. From that powerful atmospheric wave entering the stratosphere to frigid temperatures here on the ground is about two weeks. The below-average temperatures the first week of December here were the result of the stratospheric polar vortex stretching down in the second half of November. Even still, we only saw a glancing blow. In the United States the core of the below-average temperatures was in the Midwest.

How long have we known about the polar vortex

The stratospheric polar vortex has been known since the late 1940s. However, it did not earn the name “polar vortex” until around 1960, according to a journal article in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Polar vortex forecast

for this winter

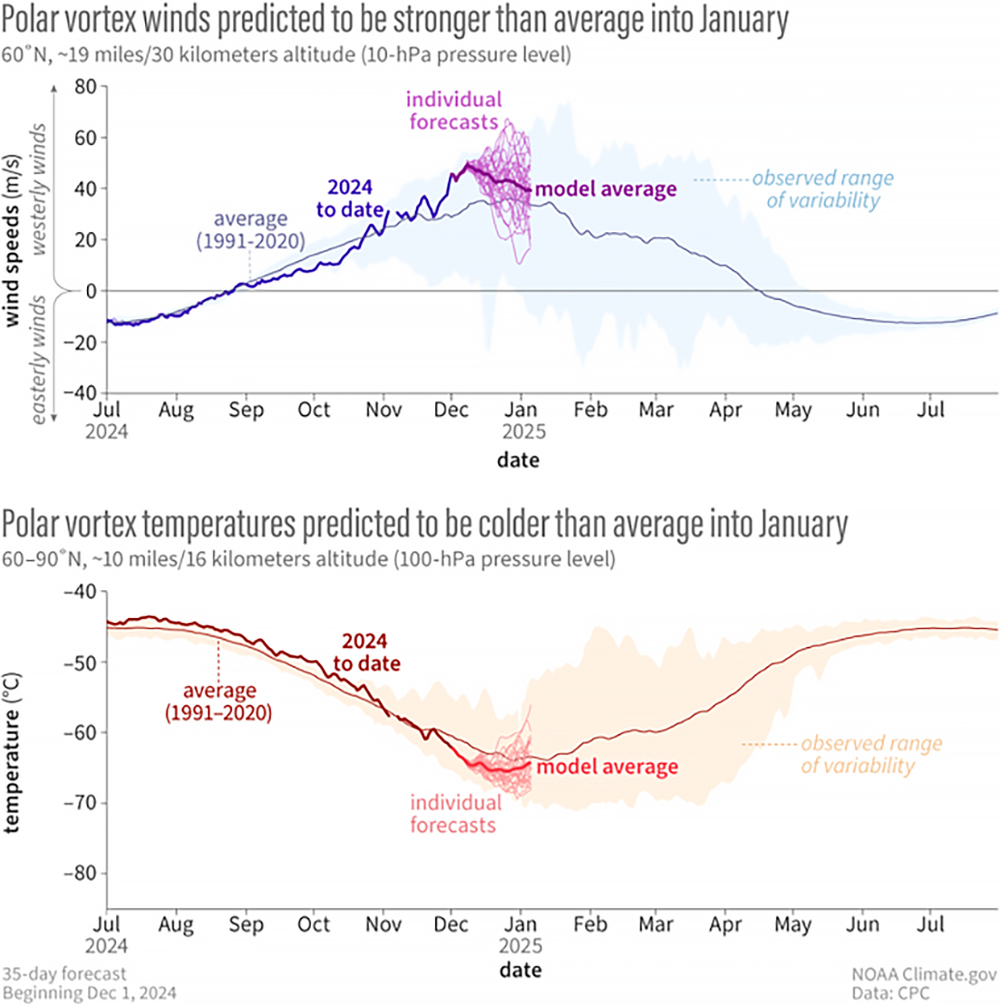

From now until January, the stratospheric polar vortex is forecast to be stronger and slightly colder than average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Dec. 4 update.

This rules out the possibility of a polar vortex split. If a split polar vortex entered the shore, you’d be talking about highs in the teens, lows in the single digits and possibly a snowy nor’easter.

However, the polar vortex will stretch into the United States this weekend. That would bring temperatures more like the North Pole for Hanukkah, Christmas and New Years holiday. That being said, don’t expect a repeat of 2017-2018, when it was so cold my ears felt like they would break off walking around Atlantic City on New Years Eve night. This should wind up staying in the western half of the United States.

Between now and at least early February, long-lasting cold and big snows are not likely here at the Jersey Shore. There is the possibility the polar vortex will stretch back down early in February, which would bring a deep winter chill for the second half of the month, according to Judah Cohen, director of seasonal forecasts for atmospheric and environmental research in Massachusetts.

Polar vortex and climate change

There is no convincing evidence that climate change in recent decades is impacting the polar vortex.

For much of the 1990s, the arctic polar vortex spun strong at the North Pole, limiting long-lasting deep cold and snow invasions. Then, in the 2000s and early 2010s, the stratospheric polar vortex weakened almost yearly. However, that weakening has happened less often since then.

Drought update

It’s been raining (and yes, snowing for a few) but our drought status remains the same. As of Dec. 6, the South Jersey shore remains in “extreme” drought, a Level 3 of four, from the United States Drought Monitor with 50.2% of New Jersey is in the same stage. Furthermore, a drought warning is still in effect by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

We need about an inch of precipitation per week just to keep up, New Jersey State Climatologist Dave Robinson said on my November Monthly Weather Roundup (you can find it on my YouTube channel). While it’s rained at least once a week since our record dry streak ended on Nov. 10, we haven’t seen enough rain to ease our drought concern. We really need more than an inch of precipitation to do that.

Winter Outlook, Live!

Our final free, in-person winter weather forecast seminar will take place in Margate on Wednesday, Dec. 18 at 7 p.m. at Margate’s Old City Hall on S. Washington Avenue. Join for giveaways, questions and answers and helpful emergency information from the Downbeach towns’ leaders. Pre-registration is appreciated. You can find that on my social media pages.

Joe earned his Meteorology Degree from Rutgers University. He is approved by the American Meteorological Society as a Certified Broadcast Meteorologist and Certified Digital Meteorologist, the only one in the state with both. He’s won 10 New Jersey Press Association Awards. You can find him on social media @joemartwx