By Bruce Klauber

Some 37 years after his passing in 1987, legendary jazz drummer Buddy Rich continues to be revered.

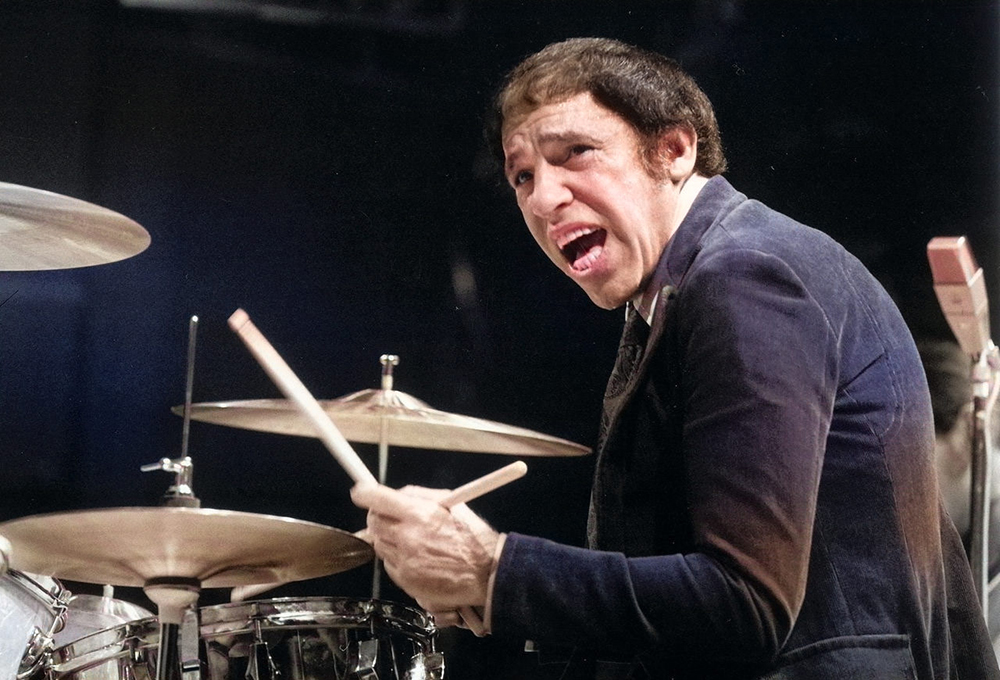

In his lifetime, at least in some quarters, he was known as “the world’s greatest drummer.” Many believe he still is. Technically, he has not yet been equaled.

And, along with Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Gene Krupa, Dizzy Gillespie and several others, he was one of the few performers in jazz history who could reach audiences who were not fans of jazz. For that we can probably thank Buddy’s friend, Johnny Carson, as the drummer made dozens of appearances on Carson’s “The Tonight Show” through the decades.

Since his passing, the marketplace has seen Buddy Rich themed merchandise including drumsticks, drum sets, books, videos, reissues of old recordings and new discoveries. The Buddy Rich legacy continues. For that we can credit Buddy’s daughter, Cathy, who continues touring with the Buddy Rich Alumni Band and has unearthed and produced many of the new audio recordings now on the market.

His incomparable artistry, musical electricity and charisma have inspired thousands of collectors worldwide to seek out every possible audio and video of the master at work, from his earliest appearances with the Bunny Berigan big band in the late 1930s, through his time as leader of his own, fiery big band which lasted from 1966 through 1987. Collectors rank his Jersey Shore performances as some of the rarest and most difficult to find. Two of them have been located, but have not yet been released to the commercial marketplace.

Rich’s earliest performances in Atlantic City were with Tommy Dorsey’s big band, where he occupied the drum chair from late 1939 until 1945. Dorsey, with Rich at the drums, appeared several times at the Steel Pier, with the most noteworthy appearance being in the summer of 1941 when the band’s boy singer was Frank Sinatra. Unfortunately, recordings of those Steel Pier shows have yet to surface.

The 1950s was an interesting time for Buddy Rich. The era of big dance bands was almost over, and modern jazz was taking its place. Rich, identified as a big band swing era drummer, adapted to the modernism shift in his own way, mainly through a series of swinging small groups that bridged the gap between the old and the new. The late 1950s were challenging for the volatile drummer, but he continued to do well on the nightclub circuit.

Several years ago, a singular recorded document of this period surfaced. It took place at a venue called the Mardi Gras in Wildwood, a spot best known in the late 1950s for booking the likes of non-jazzers like Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. Rich was booked there for a week in late July of 1958, leading a superb small group that featured the highly underrated Sonny Criss on alto saxophone.

Issued on a CD was a recording of an entire evening, likely made by someone in the audience. It’s well worth having, if you can find it. Buddy Rich gives it his all on the drums, despite playing to what sounds like a sparse crowd.

In early 1959, the frustrations and the years of one-nighters caught up with Buddy Rich when he suffered a massive heart attack, the first of several throughout the years. The word from his physicians and others was that he would never play again. As always, Buddy Rich proved all of them wrong.

He was back at the traps in two months, and in that year, signed a new contract with Mercury Records. His first outing for Mercury was a now-iconic session with modern jazz drumming great Max Roach. Roach, one of the fathers of modern jazz drumming, was at the top of his game then. Rich, on the other hand, was viewed as old hat. Again, Buddy Rich prevailed. To put it politely, he carved Roach.

The second session was an all-star big band date with Ernie Wilkins. “Richcraft” has been issued various times on various labels, but it still stands as one of the finest examples of Buddy Rich driving a big band.

There has been a lot of talk among collectors that Rich actually took a version of his large ensemble to the shore in the summer of 1959. One of the stops, according to discographers, was the Steel Pier, but until very recently, there was no audio record of such a performance.

Fortunately for collectors, a half-hour radio broadcast, live from the Steel Pier’s Marine Ballroom and recorded on July 31, 1959 (the band was there for the entire first week of August) has surfaced. It’s quite a session, and though it hasn’t been issued on CD yet, it surely will.

In 1966, Buddy Rich decided to form a big band. He was told repeatedly that no one cared about big bands anymore and that such a venture was bound to fail. He defied the odds yet again, as the big band was a tremendous success. On Aug. 3, 1969, The Buddy Rich Big Band was part of the now legendary Atlantic City Pop Festival.

The fest has been covered in great detail in these pages, but an explanation is in order as to just why a jazz drummer like Buddy Rich was booked to perform that day with the likes of Canned Heat, Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker, The Moody Blues and The Mothers of Invention, who were also on the bill. During that time, the repertoire of The Buddy Rich Big Band began to include a number of rock and funk songs, and many were part of a recording called “Buddy and Soul.”

The goal of Rich and his management was to reach out to a younger audience via a rock-themed repertoire, and it worked. Rich and his crew were often booked at other festivals like this and at spots like the Fillmore East and the Electric Factory. And just how good was Buddy Rich at playing rock and funk? Years after Rich’s passing, fellow drummer Mel Lewis deemed Buddy Rich “the greatest rock drummer who ever lived.” An overstatement, perhaps, but Rich played the heck out of those rock numbers, and when he took a solo, youngsters’ jaws dropped.

The band’s final appearances in Atlantic City found them second-billed to singers. The group appeared at the Boardwalk’s Golden Nugget in September of 1985, and played six songs – lengthy for an opening act – before the star of the show, jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, came to the stage. Rich’s set was shorter a year later when he opened for Suzanne Somers at Harrah’s.

On April 2, 1987, Buddy Rich died. Even today, those who remember the master insist that there will never be another one like him.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.