By Chuck Darrow

The discussion of Atlantic City’s important role in the careers of immortal entertainers usually begins with the summer, 1946 pairing of the then-unknown Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis at the storied 500 Club on Missouri Avenue. While that may be the most dramatic and indelible tale, it is hardly the only one.

From the end of the 19th century, Our Town has been a key part of the nation’s entertainment ecosystem. More to the point, it was where some (then-unheralded) performers took early—sometimes odd—steps on their journeys toward stardom. Below are examples of how Atlantic City provided a place for two young artists to develop their talents and ultimately become individuals whose names and bodies of work continue to resonate.

W.C. Fields

Born William Claude Dukenfield in the Philadelphia suburb of Darby, Pa. in 1880, Fields was an 18-year-old juggler when, in the summer of 1898, he was hired for the summer by Fortescue’s Pier, a long-gone amusement center located on the Boardwalk at Arkansas Avenue (later the site of Million Dollar Pier; today it’s The Playground). While juggling was his main occupation (by his own account, Fields would do as many as 20 performances a day that summer), his bosses at the amusement pier also used him in a more unusual—and profitable—way.

It was part of the local culture of that era (as it likely remains today) that when ocean bathers had the misfortune of being swept into the sea beyond their ability to make it back to shore on their own, their rescues by lifeguards tended to draw sizable crowds of onlookers. In the great spirit of American enterprise, the pier’s operators hit on a scheme to take advantage of the public’s unyielding interest in such human drama.

In his definitive 2005 biography, “W.C. Fields,” James Curtis quotes Fields reminiscing about that fateful—and waterlogged—summer.

I would swim out in the ocean, and when I got out some distance, I’d holler “help,” go under, come up after a moment, spitting a lot of water. Then two or three men, all plants, waiting on the shore, would swim out to me, battle around me while everyone would run up to see what the excitement was. “Someone’s drowning!” they’d all begin shouting and start a ballyhoo. Then when the crowd was big enough, the men would drag me in. I’d be spitting water here and there and sometimes one of the bystanders would get a face-full. Three or four fellows would carry me then right into the pavilion with the crowd following after us to see what was going to happen. Next, they throw me across the table and begin working on me. But by this time, the band would be playing, and the funny Irishman would walk out on stage. So they’d all begin to look at him and forget about me. Finally, I get up weekly and slough away.

Fields had done his job, as the folks in the crowd would invariably buy refreshments (adult and otherwise), thus increasing that day’s take at the pier.

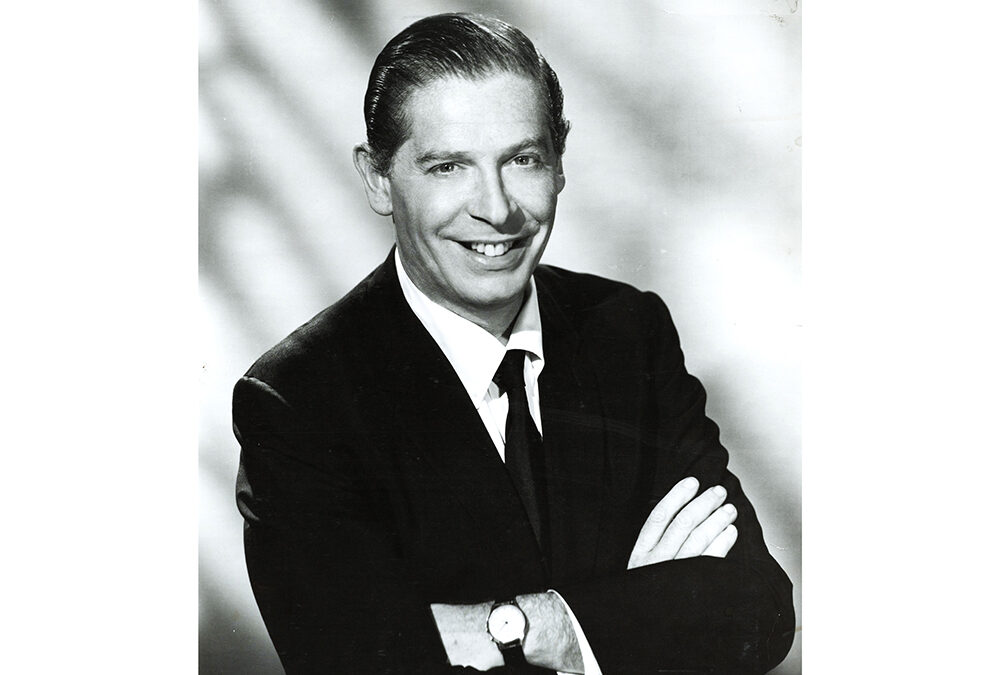

Milton Berle

Fields ultimately went on to a glittering career on Broadway and then, in the 1930s and ‘40s, as one of Hollywood’s marquee comics. But his impact on show business never came close to the role Milton Berle played in the development of television into history’s most powerful and culture-forging, pre-digital medium. But almost three decades before he became everyone’s “Uncle Miltie,” he was a 12-year-old show biz vet (thanks to his mother, Sarah, who, various reports suggest, pretty much created the “stage mother” archetype).

In 1920, the young Berle won a role in a revival of “Floradora,” a beloved turn-of-the-20th century musical that included the then-famous “Floradora Girls,” who performed (along with a male chorus line), the popular song, “Tell Me Pretty Maiden.” For the 1920 revival, a second rendition of the song was added, this time delivered by a troupe of younger performers, Berle among them. As was common back then, this production had its pre-Broadway premiere in Atlantic City, specifically at the Globe Theater, which was located at Delaware Avenue and the Boardwalk (where Showboat Hotel sits today; it later became a burlesque house featuring the top striptease artists of the time).

Unbeknownst to anyone involved in the production, before the opening-night curtain rose, Berle’s mother told him to begin his choreography on the wrong foot, knowing the awkwardness would create a comedic moment that the audience would find endearing, and draw attention to her son.

According to Berle’s 1974 book, “Milton Berle: An Autobiography,” the ploy worked just as Mom predicted, but also caused the show’s producer, the famous J.J. Shubert, to contemplate murdering the pre-pubescent upstart. But in the book, Berle noted that despite his anger, Shubert acknowledged the delight of the audience and insisted Berle keep the shtick in the number. That took the comedic titan to Broadway and launched in earnest his legendary career.

Chuck Darrow has spent more than 40 years writing about Atlantic City casinos.