By Chuck Darrow

Each day, an untold number of folks drive past the all-but-abandoned tract of land that sits at the intersection of Albany and West End avenues. It’s quite likely most of these people don’t give a second thought about what is the largest undeveloped tract of land in Atlantic City—as well as a landmark of inestimable historic value that played a key role in the development of air travel in the United States and beyond.

Bader Field today is mostly known as the site of the ill-fated Sandcastle baseball stadium—a symbol of Our Town’s legal-casino-era’s hopes, dreams and, sadly, realities. But a century or so ago, it was at the forefront of the nation’s rush to modernity.

As early as 1910, hobbyists were using the space; some of the world’s first air shows were staged there. And when it began official operation on May 10, 1919, it did so as a typical, privately owned aviation facility—or “airport”–the term which was created specifically for the facility. In 1922, the Atlantic City Municipal Airport was purchased by the city—the first such facility to be owned by a government entity. It kept that name until 1927 when it was renamed in honor of the recently deceased Mayor Edward Bader.

As a state-of-the-art amenity, the airport was crucial to making—and keeping—Atlantic City the “World’s Playground” during the decade that saw its zenith as a pre-legal-casinos resort destination. It was also a magnet for the generation of aeronautic pioneers who were crucial to spreading the popularity of early air travel: In October 1927, Col. Charles Lindbergh visited Bader Field just months after his epochal transatlantic flight.

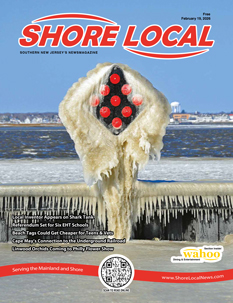

Charles Lindbergh and his Ryan monoplane, the Spirit of St Louis. Photo: Getty Images

“The Atlantic City airport has good possibilities and is in an ideal location to the city proper,” was “Lucky Lindy’s” appraisal. “In fact, it is the best-situated in that respect, I think, than any I have yet encountered.”

Lindbergh returned to Bader Field four years later as a guest of legendary World War I fighter pilot Eddie Rickenbacker, who presided over festivities celebrating the takeover of Airport operations by Eastern Airlines, which he ran at the time. Also on the guest list was Amelia Erhart, the groundbreaking female pilot whose 1937 disappearance in the South Pacific remains one of history’s most perplexing cases.

Another famed air jockey of the day also made the Bader Field scene that year: A daredevil named William Swan earned his aeronautic posterity by using the airport as his site when he became the first person to fly a rocket-propelled aircraft.

And speaking of firsts, it was from Bader Field in 1934 that Charles Alfred Anderson, who is celebrated as the father of Black aviation, and an Atlantic City physician, Dr. Albert E. Forsythe, took off on their flight that made them the first African American pilots to complete a transcontinental round trip (to and from Los Angeles). Remarkably, the pair accomplished this precedent-setting feat without such accessories as radios, landing lights or any kind of “blind-flying” equipment.

In late-1941 (just prior to the Dec. 7 attack) Bader Field was where the Civil Air Patrol was chartered—its mission being the scouting of the Atlantic Ocean for German submarines (one sortie actually saw weapons-equipped planes destroy a Nazi sub).

Bader Field’s golden age wasn’t limited to the aviation world. In 1921 heavyweight boxing icon Jack Dempsey trained there for his fight against George Carpentier. And when wartime restrictions prevented the New York Yankees from conducting spring training in Florida in 1944 and ’45, the Bronx Bombers set up shop at the airport.

As with Atlantic City itself, the post-war years saw Bader Field’s star start to dim. Ironically, one reason was air travel itself—or more specifically the increasing ability of middle-class Americans to avail themselves of affordable fares to more exotic climes, like Florida and Southern California. Another issue was the ever-expanding size of new generations of planes, which made them too big to land at Bader.

The final nail in the airport’s coffin as a viable facility was the decades-long evolution of what was a naval airbase built in the 1940s into what is today Atlantic City International Airport in Egg Harbor Township. It was officially closed to air traffic (virtually all of which at that point was of the small, private-plane variety) on Sept. 30, 2006. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

Of course, there was the Sandcastle (later Surf Stadium), a 5,500-seat ballpark built for the independent-league baseball team, the Atlantic City Surf, that opened in 1998. Attendance never came close to its backers’ projections, and the Surf called it a day before the start of the 2009 season. The stadium continued to be used for scholastic contests, and as a concert venue.

In recent years, a number of redevelopment proposals have been floated for the now-vacant, 140-acre site, including a mixed-used concept submitted by real estate kingpin Bart Blatstein, owner of the Showboat Hotel/Island Waterpark complex on the eastern end of the Boardwalk.

In 2023, Mayor Marty Small officially signed off on a plan pitched by DEEM Enterprises for “Renaissance at Bader Field,” a $2.7 billion endeavor that would emphasize automobiles with various themed exhibits and a 2.44-mile Formula One racetrack. The blueprint also includes condominiums and commercial outlets.

As you read this, there seems to be little movement: An online search found that the most-recent mention of the project is a release from Small’s office dated April 5 of this year which states: “Meetings are ongoing with DEEM Enterprises on a Bader Field redevelopment agreement, which the city remains hopeful will happen sooner than later.”

Which means the future of Bader Field fittingly remains, if you will, up in the air.

Chuck Darrow has spent more than 40 years writing about Atlantic City casinos.