By Bruce Klauber

If Louis Prima invented the concept of the Las Vegas lounge entertainer, then singer/pianist Buddy Greco defined it. But those who remember Greco as the penultimate “lounge lizard,” known for his up-tempo version of “The Lady is a Tramp,” will be surprised to know that he was also a superb jazz pianist who spent several years with Benny Goodman’s band during Goodman’s failed flirtation with bebop and modern jazz.

The Philadelphia-born Greco took to the piano at a young age and worked in and around the Philadelphia area, sometimes singing while playing piano, when he caught the attention of the mercurial King of Swing circa 1948.

At that time Goodman was regarded as passé in some circles, though he was still one of the biggest names in the business. But the swing era, which Goodman helped invent, was effectively over by 1945, as it gave way to the modernism of beboppers like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Some bandleaders, like Woody Herman, modernized their approach with the advent of bop. Goodman, however, stuck to the old style and his old hits until the marketplace almost forced him to evolve. While Goodman appreciated the modern players, he was so harmonically and rhythmically grounded in the swing style that changing the way he played and thought about the clarinet was almost impossible.

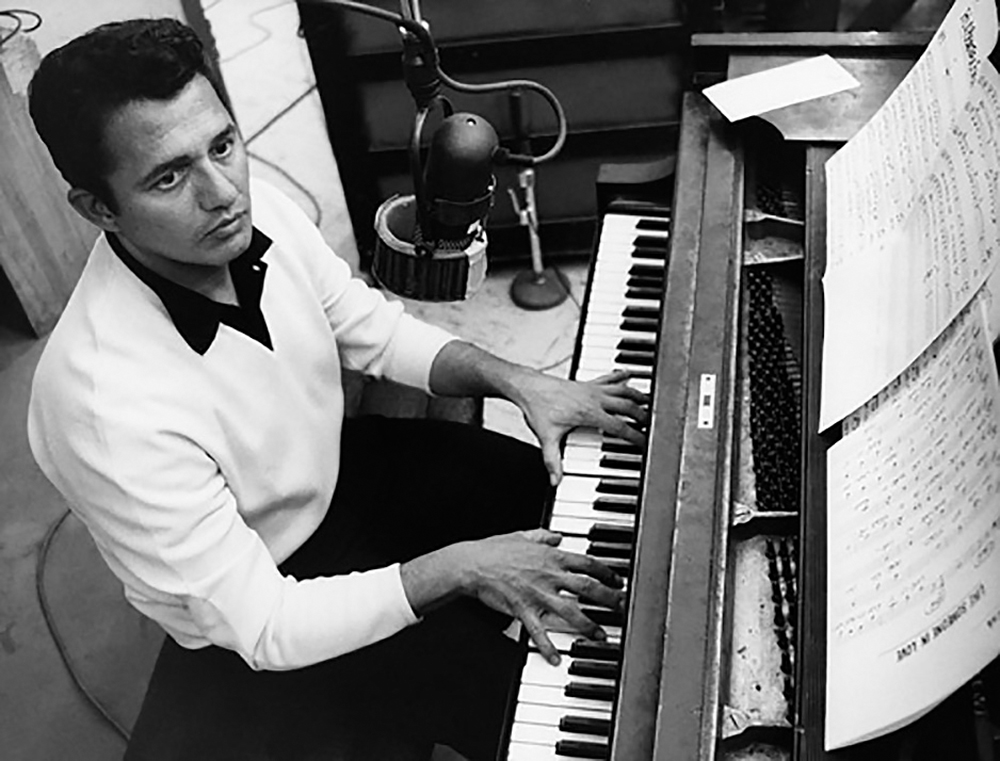

Buddy Greco

1966

© 1978 Ed Thrasher

Goodman couldn’t ignore the rising influence of bop, so by 1948 or thereabouts, he decided to take the plunge into modernism and hired superb bop-style players like saxophonist Wardell Gray, trumpeters Fats Navarro and Doug Mettome, drummer Sonny Igoe, and a 16-year-old pianist and singer from Philadelphia, Armando Joseph “Buddy” Greco.

In later years, Greco became a junior member of Frank Sinatra’s “Rat Pack” and a mainstay of the Las Vegas lounges. He was a frequent visitor to Atlantic City from the early 1980s through the early 1990s, appearing often in the lounges at Caesars, Elaine’s lounge within the Boardwalk’s Golden Nugget, and The Claridge.

I first came upon Buddy Greco in the lounge at Caesars. I cornered him during a break and told him that I had always enjoyed his work in Goodman’s short-lived bop band and that I loved his interaction back then with soloists like Wardell Gray and Doug Mettome. He was really surprised that I knew about such things.

“You mean you don’t want to know about my friendship with Marilyn Monroe?” he asked. “That’s what everyone wants to know.”

I answered in my best jazz vernacular, saying, “No, man. I want to know about Wardell and Fats.” We became, if there is such a thing, instant friends.

I spent almost every break with him at Caesars and he regaled me with stories about Goodman and the modernists within the band.

“Benny treated me like a son,” he told me. “He gave me free rein to sing, to arrange, and to play bop piano as I saw fit. He must have seen something in me, though I’m still not sure what.”

There was no doubting the fact that Greco had a pretty large ego, but when I looked at his track record, my thought was that he had earned the right to think highly of himself. He sold more than a million copies of songs like “The Lady is a Tramp” and “Around the World,” recorded 60 albums, was a regular on television through the years, co-hosted a CBS television series with George Carlin and Buddy Rich, and was a major celebrity in England. Given all that, the lounge at Caesars should have been packed. It wasn’t and Buddy Greco was unhappy with the way he was being publicized at Caesars.

By that juncture, Buddy knew as much about me as I did about him. Although he knew I was a drummer and a singer, he also knew that I was a columnist for Atlantic City Magazine, and that I might have some kind of influence in Atlantic City entertainment circles. On one break that I’ll always remember, he flat-out asked me the following: “Bru (his nickname for me), nobody knows I’m here in this lounge. You’ve got to call the president of Caesars and tell him to get signs put up all over this place to let people know I’m in the lounge.”

“Call the president?” This was one heck of a request. Sure, I wanted to help, but I had no idea just how much I could do. I could only say, “I’ll do what I can.”

I made a number of calls the next day, including one to my contact within Caesars PR department. I told them that Buddy was unhappy with how he was being promoted at Caesars, that if he were publicized properly he would pack the lounge every night of the week, and that if Caesars didn’t do something to let people know he was there, there was a chance that Caesars might lose him.

The next night, there were signs all over the Caesars casino floor, lobby, and everywhere else. Buddy Greco was happy.

In the next several years, our friendship grew. He wrote one of the blurbs to my first book on Gene Krupa, and always invited me up to the stage to sing or play wherever he was in Atlantic City. Wisely, I stuck to the drums. There was no way I was going to follow a Buddy Greco vocal with a song of my own.

Surprisingly, for someone so grounded in jazz and jazz improvisation, his shows never varied. He sang songs and played the same piano solos in the same way, note-for-note, every night. It never varied. Several of us, including the great pianist, Dean Schneider, could “do Buddy” note for note if we had to.

As the Atlantic City entertainment scene changed, Buddy Greco rarely came to Atlantic City. He spent a good deal of time in England, produced and starred in critically acclaimed tributes to Frank Sinatra and Peggy Lee, opened his own club in Palm Springs, and thankfully, returned to his jazz roots late in life. His 1992 album for the Bay Cities label, “Round Midnight,” is superb as is “Jazz Grooves,” released by the jazz-focused Candid label in 1998.

Buddy Greco always had energy to spare and he worked, mainly in England, until a year or so before his passing in Las Vegas at the age of 90 in 2017.

He once told me that Benny Goodman called him when he was a teenager. He told Goodman that he had better offers and wasn’t sure what to do. Greco’s father told his son, “You go with Mr. Goodman and learn your craft. You’re going to thank me.”

Turns out his father was right and Buddy Greco did, indeed, have the chance to thank his father.

In Atlantic City, he performed at THE DUDE RANCH, corner of Connecticut Ave & the BOARDWALK. I worked in a luncheonette a few doors away, Buddy came in for coffee and I served him a number of times. This was 1954-55