By Bruce Klauber

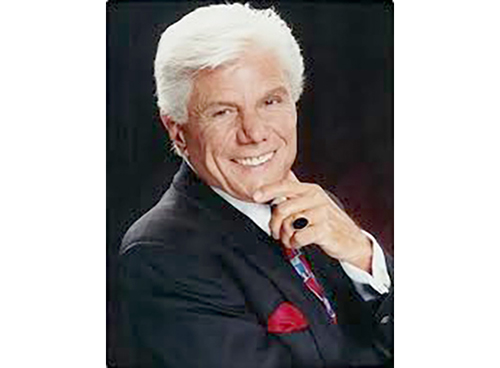

The late, great Frankie Randall was a force of nature. He was a singer, pianist, composer, conductor, recording artist and a talent buyer who helped put the Boardwalk’s Golden Nugget hotel/casino in Atlantic City, and the Nugget in Las Vegas, on the map as the place to be booked.

Because he was trusted and held in such high regard by his fellow entertainers, he was able to lure performers like Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin away from Resorts International in the early days of legalized gambling in Atlantic City, and away from Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to the two Nugget operations.

A coup like that wasn’t easy. The Atlantic City Boardwalk’s Golden Nugget, which opened in 1985, was the new kid on the block at the time. The Vegas Nugget, located in the heart of Freemont Street, that city’s honkytonk central since 1946, had been undergoing extensive renovations since the early 1970s.

Under the ownership of Vegas visionary Steve Wynn, the downtown Nugget actually received a four-diamond rating from the influential Mobil Travel Guide in 1977. By 1984, a brand new tower was added and the venue was ready to pitch top stars like Frank Sinatra.

When the Nuggets were ready, so was Frankie Randall.

The deal that he and Wynn offered Sinatra, just to name one, was unique. In addition to performing, Mr. S. would appear at special events for high rollers and would serve as television spokesperson for the hotel/casino. It was, as they say, an offer he could not refuse.

Randall didn’t start as a deal-making talent booker. Born Franklin Joseph Lisbona in Passaic, New Jersey, he began taking piano lessons at an early age. By 13 he was already taking jobs playing piano.

Child prodigy or not, Randall’s father insisted that he go to college and learn something “other than music,” just in case. He graduated from Fairleigh Dickinson University with a bachelor’s degree in psychology, which would pay off for Randall later.

After graduation, he landed a job at Jilly’s in New York City, one of Sinatra’s favorite haunts. Mr. S. was wowed by Randall’s talents as a pianist and singer, and took him under his wing, something he hardly ever did.

This led to a recording contract, first with Roulette Records, later with RCA. There were appearances on “The Tonight Show,” and other variety shows of the day. He also performed on high-visibility shows in Las Vegas lounges, and at venues on the still-thriving nightclub circuit.

He made appearances in two films in the latter 1960s, and was the host of one of Dean Martin’s summer replacement television programs.

He was a good, swinging, exciting singer, and when he put his mind to it, was a fine jazz pianist. But in 1964, things were changing via the arrival of The Beatles.

It took a year or two, but little by little, middle-of-the-road pop singers like Randall, Jack Jones, Peggy Lee, Joe Williams, Tony Bennett, Steve and Eydie, and many lesser names were losing their recording contracts and were forced to hang on to those venues, mostly in Las Vegas, that still booked straight-ahead pop acts. As the late Julius La Rosa once told me, “It used to be that we were thrilled to fill a 450-seat nightclub. After The Beatles came in, unless you could fill a 15,000-seat arena, you were nothing in this business.”

Because Frankie Randall was talented in so many aspects of the business, he did better than some others. He recorded for RCA as late as 1968, with “The Mods and the Pops,” a title which was a nod to what was going on musically at the time.

Las Vegas, fortunately, was still booking some of the stalwarts in their lounges, including Frankie Randall. In that he was known as a Sinatra protégé, and was frequently working in Vegas, he forged a relationship with Steve Wynn.

Whatever anyone thinks of Wynn, he was smart. He knew Randall had the connections, the savvy and the smarts – remember, Randall had that degree in psychology – to lure top-name performers to his hotel/casinos.

Randall stayed on at Atlantic City’s Golden Nugget for a few years after the venue was purchased by Bally’s, and still performed there from time to time in the lounge and on the main stage, mainly doing a Sinatra tribute show. He hung on as a talent buyer in Vegas until the business began to change in favor of mega-pop acts and spectacular production shows.

In later years he had the distinction of being informally known as “Frank Sinatra’s house pianist,” playing often at parties and get-togethers at the Sinatra compound in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “He called me his favorite piano accompanist,” Randall told The New York Times.

Frankie Randall won several awards, including a star on the Palm Springs’ Walk of Stars, a 2002 induction into Las Vegas Casino Legends Hall of Fame, and the Amadeus Award, given to him by the Desert Symphony in 2013. He deserved them all.

Frankie Randall was a personal and professional friend of mine for some years. He was a gem: honest, caring, approachable. He couldn’t do enough for you.

I saw him onstage with Frank Sinatra, and I saw him playing an upright piano in the lounge of Atlantic City’s old Sands. Though those two performing situations may have been miles apart, they weren’t for Frankie. He was the same smiling, enthusiastic and swinging performer wherever he was, and whatever the gig was.

Frankie Randall died at the age of 76 on Dec. 28, 2014.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.