By Bruce Klauber

Atlantic City locals refer to it as “The Monument.” Visitors frequently view it as something that makes one of the entrances to Atlantic City a traffic challenge. And hundreds of thousands of residents and visitors drive or walk by having no clue what it actually is.

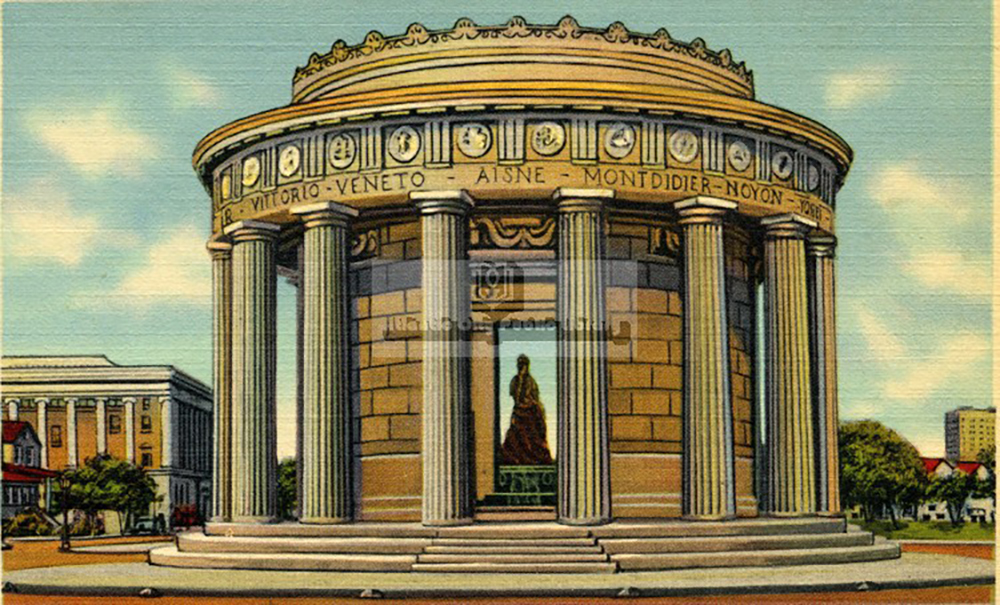

In reality, the Greek Temple Monument, located at South Albany and Ventnor avenues, is a World War I memorial built between 1922 and 1923 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places on Aug. 28, 1981.

It didn’t start out as a memorial. The original idea, circa 1907, was to simply build something decorative. The city hired the architectural firm of Carrère and Hastings, the outfit responsible for designing the mid-city branch of the New York Public Library.

The project, on paper, moved along slowly and existed mainly as just a novel idea until the whole thing was delayed indefinitely by the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

In late 1917, the year the United States entered the war, it was decided that the original idea for a decorative structure would be modified to serve as a memorial to those who died in the war.

The first order of business was for the Atlantic City Commissioners to buy the land at Albany and Ventnor, which was owned by the then-massive West Jersey and Seashore Railroad Company. After the purchase was finalized, the city came up with $150,000 to build the structure. A Monument Commission was formed in early 1920, the idea and the plans were quickly approved and the project was ready to be built.

Inside is a 9-foot bronze statue that bears the title, ‘Liberty in Distress.’

It was constructed by a long-forgotten company called Emile Diebitch, Inc., and the particulars of the structure are extraordinary.

Made from Indiana limestone, slate and bluestone, the monument is 124 feet in diameter, has 16 Doric columns, and originally had four entrances, which were eventually fenced in circa 2008.

On the outside, above the columns and carved in stone are the names of the World War I battles in which Atlantic City soldiers saw action. There are also the shields of the Army/Navy Aviation and the Marine Corps.

Inside is a 9-foot bronze statue, designed by Frederick A. MacMonnies which bears the title, “Liberty in Distress.” Around the top of the circular interior wall is the inscription, “This Monument Was Erected In 1922 by the City In Honor of Her Citizens Who Served In the World War 1917-1918.”

The first controversy surrounding the monument had to do with MacMonnies’ statue. Installed at a cost of about $25,000, it depicts a mourning Lady Liberty over a fallen soldier.

The Brooklyn Heights-born MacMonnies had an international reputation, and was highly-regarded in France as a sculptor who was a primary proponent of the neoclassical Beaux-Arts school.

Five years after his statue was installed in Atlantic City, the city fathers discovered that MacMonnies built something similar – a statue for the French government called “France Aroused.” The issue was that Atlantic City Commissioners thought they were paying for something exclusive, when the statue was anything but. MacMonnies countered by saying the French work was larger.

There were other controversies over the years. When the New York Art Commission visited the monument in 1949, they were appalled by how seriously vandals had defaced it. That led to the installation of floodlights, mainly in the monument’s interior, specifically to illuminate the MacMonnies statue.

Then there was talk over the years about moving the monument to improve traffic flow. The first serious discussion took place around 1961, when the city’s traffic supervisor strongly suggested that it be moved up the block and just across from what was then Atlantic City High School.

A year later, it almost happened. There was a vote to tear down the temple, keep the MacMonnies statue, and move it to the nearby O’Donnell Memorial Park, home of various other war memorials, complete with a marble wall that would contain the names of those who served in World War I and II. That almost happened, until the city realized that it would cost more than $60,000 – $637,000 in today’s funds – to demolish the temple and move the statue. That never happened, and a similar plan floated in 1965 didn’t happen, either.

All the talk about tearing down the temple and moving the statue died down with the advent of casino gaming.

The monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981.

In 1988, the monument was restored and rededicated, and on May 12 of that year, a bronze plaque was installed with the names of everybody involved in the project. Despite that, in the 1990s, there was again some talk about moving the monument, specifically to improve the traffic flow to the hotel/casinos.

Again, nothing came of that idea, and in the late 1990s, the city’s Urban Beautification Committee, dedicated to improving the monument, facilitated new landscaping and lighting. In 1998, the monument and the statue within were rededicated.

There are other impressive memorials in and around Atlantic City, but none as extraordinarily and impressively imposing as The Greek Temple Monument. And like the city itself, the structure known to one and all as “the monument,” has survived.

Special thanks to Linda Richardson-Korman for helping to facilitate the publication of this article.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.