By Julia Train

Lauren Seyler believes that the search for life on other planets begins on Earth, at the bottom of the ocean.

This summer, Seyler, a Stockton University assistant biology professor–who also studies astrobiology– spent a week off the coast of Chile co-leading a research expedition studying the ocean floor near the Atacama Trench.

Seyler joined a group of about 20 scientists on a 363-foot ship owned by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, a private nonprofit organization that supports marine research.

After three years of planning, Seyler was able to conduct her own research using state-of-the-art equipment.

While she had to cover her own expenses to actually get to Chile, the institute covered all of the costs associated with running the ship, like getting the scientists to where they need to go, paying the crew to pilot the ship and the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and taking care of and feeding those on board.

“Their ship, the Falkor (too), is just incredible. It’s a state-of-the-art ship. It was the largest oceanographic ship I had ever been on, and just the amount of resources available to us as scientists [and] the comforts provided to us just were just absolutely unparalleled,” said Seyler.

The group consisted primarily of scientists from Chile and Spain, with a handful of Americans. Each applied to be on the ship for a different reason.

There were geologists on board who were interested in looking at the geology of the sea floor off of the coast. Other scientists were looking to catalog marine life, collecting specimens for the Chilean Museum, including sea stars, sea cucumbers, clams and brachiopods.

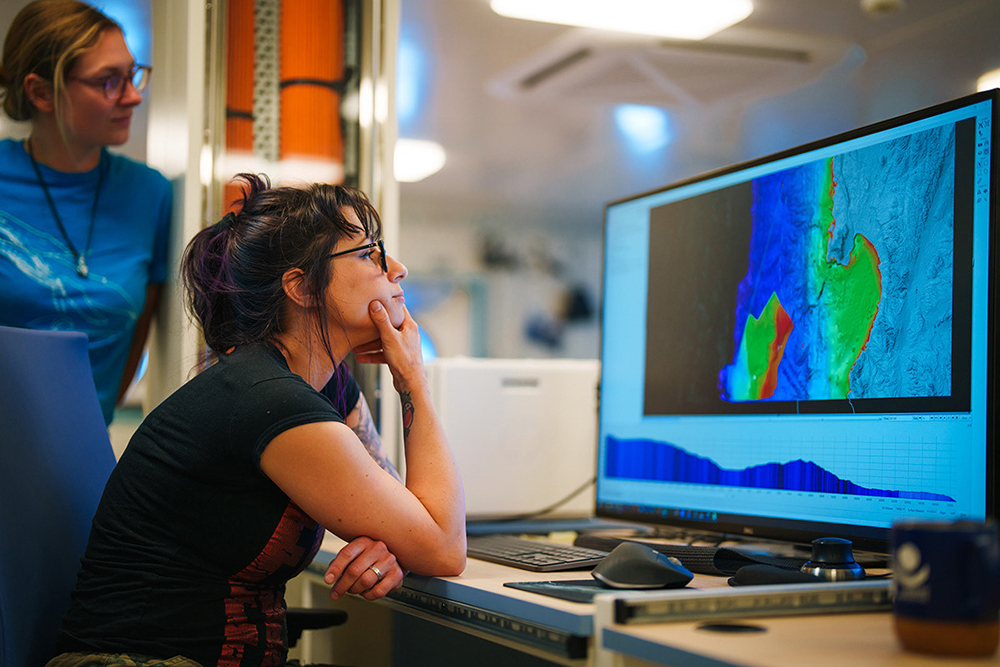

Stockton Assistant Biology Professor Lauren Seyler looks over some ocean-floor mapping data off the coast of Chile in an effort to locate methane seeps at the bottom of the Atacama Trench. Photo credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute.

Methane seeps and life on other planets

A bunch of attendees, including Seyler, were astrobiologists aiming to find methane seeps, areas where methane escapes from rock into the ocean above it.

Methane seeps can be found in several locations around the world, but what makes the location Seyler was searching so special was the fact that it’s at a convergent boundary, where two plates of the Earth’s crust collide

At the spot, one plate of the seafloor slides underneath the other, which contains the continent of South America. As one slides underneath the other, it causes the plate on top to buckle, crack and form ridges. The rocks release methane gas as they break down, melt and change.

“We, based on the data, figured that a lot of the energy for these ecosystems was likely coming from methane seeps,” said Seyler. “We were all really interested in how studying the seafloor in this particular region might help us find life on other planets. If we find life on another planet…we’re likely going to find it associated with water. The search for life is the search for water.”

Seyler said that looking at seafloor ecosystems fueled by chemical energy, as opposed to sunlight, will help scientists to understand how life in the deep ocean functions and develop ways to look for it in other contexts, such as on other planets.

“We were interested in this particular part of the world, because it’s off the coast of the oldest and driest desert in the world, the Atacama Desert, which is an analog for the surface of Mars,” said Seyler. “People have been studying the Atacama for years as a way to understand how life can survive in these incredibly dry conditions that we may find on the Martian surface, [which is] cold, dry and dusty.”

A sea pig walks among some clams found at the bottom of the ocean floor near the methane seep off the coast of Chile. Photo credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute.

No seeps seen

The original plan was to spend two weeks at sea off the coast of Chile, but there was an issue acquiring the permit, leading the team to lose half of their ship time.

When they finally got out to where they needed to be, the scientists scrambled to meet everyone’s objectives, Seyler said.

Every night, the ship would pass over the surface of the ocean, running the multi-beam sonar, looking for places to search for seeps.

Then, in the morning, the scientists would take all of the data, clean it up and look at it and choose locations to search, and then drop the ROV down and follow it for hours, waiting to find something.

“It’s basically like a slow hike in the dark, because we were thousands of meters below the sea surface [and] it’s completely dark down there,” said Seyler. “The ROV lights up this small area in front of you–and you have the sonar–but you’re just slowly crawling along hoping that you’ll trip over something cool based on the data.”

The scientists on the ship often wound up working 20-hour days due to the length of time it took to get the water sampler and the ROV all the way to the bottom and back up, sampling the whole way after that. Then, they had to spend hours searching along the bottom.

“You’re essentially operating a robot with a joystick from thousands of meters above it. So the scientists are sitting in this control room [instructing] the ROV pilots [on where to go],” said Seyler. “So we were switching off days between going on these long walks along the seafloor, looking for seeps and not stopping unless we saw something.”

Once the ROV came back up on deck, the samples had to be removed, processed and properly stored, so they wouldn’t deteriorate.

Seyler’s team didn’t find anything…until day four.

‘It was such a relief.’

The expedition was almost finished and the team spent the majority of it searching the sea floor without finding anything.

They’d been searching for 12 hours that day when, all of a sudden, they found a bed of clams that are only found by seeps.

So, they kept looking and came across a methane seep that produced all kinds of sea life, including ashy, grey- and black-colored mats of bacteria, 6- to 7-inch clams, tube worms and a species of sea cucumber called a sea pig.

“It was such a relief. In addition to being extremely exciting, it was like I could breathe,” said Seyler.

They put the ROV down, took some samples and looked around some more. The more time they spent at the spot, the more they found.

Seyler said they took as many samples as possible before heading back to shore.

Now, she’s waiting for funding to analyze the microbial communities in the mud she collected and figure out how they’re using methane as a source of energy.

“Some of the samples she was able to collect on this expedition she’s bringing back to Stockton University, and students who work with her are going to be able to do experiments and studies on those samples,” said Amanda Norvell, dean of Stockton’s School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. “She was able to bring a lot of material back with her, and students are going to be able to engage with that, doing, you know, real-world science from now moving forward.

Julia is a recent Rider University graduate, where she studied multiplatform journalism and social media strategies. In her spare time, she enjoys reading, trying new coffee shops, photography and the beach. She can be reached at juliatrainmedia@gmail.com or connect with her on Instagram @juliatrain