By Bruce Klauber

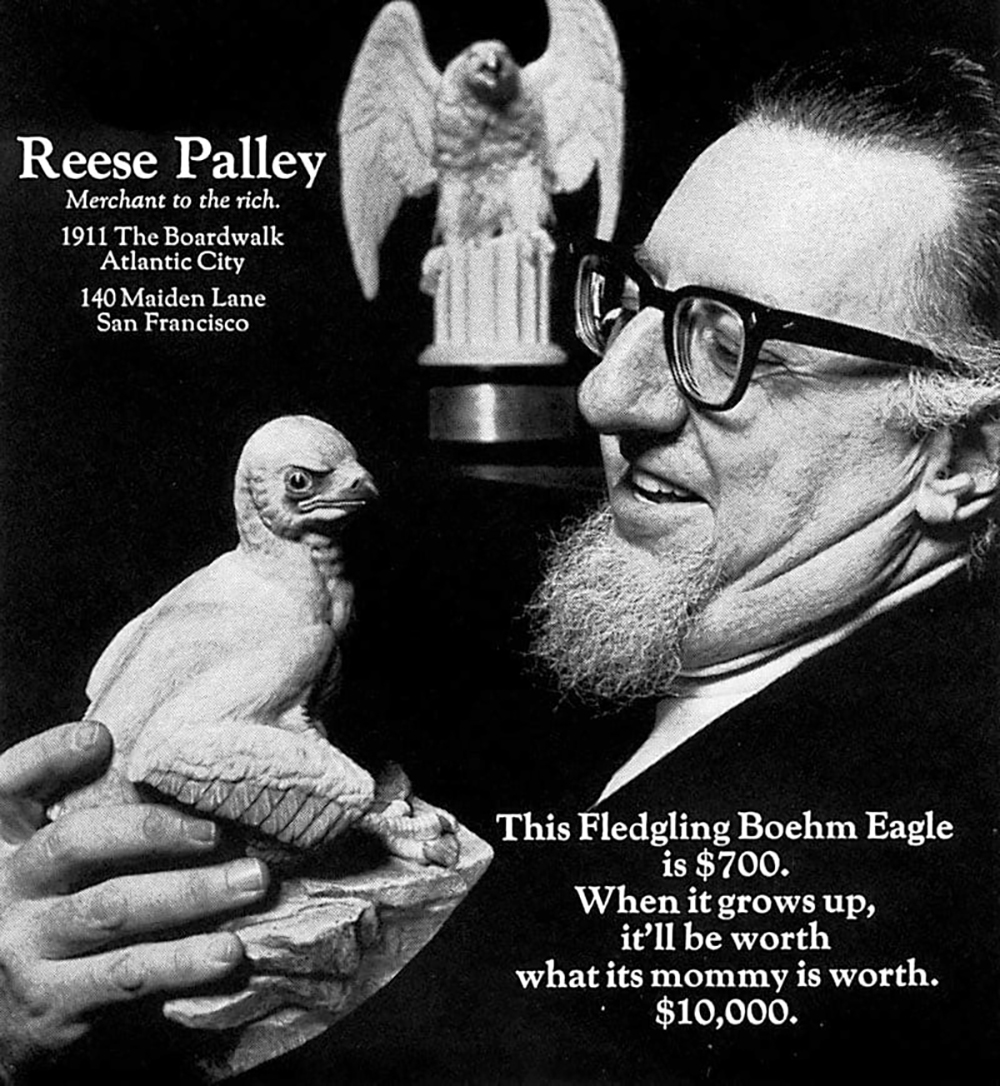

Atlantic City’s late Reese Palley was an art dealer, businessman, writer, author, sailor, salesman extraordinaire, and a visionary. Above all, he was a certifiable eccentric.

Though some of the many claims that Palley made through his lifetime have to be taken with a grain of salt, we are certain that he had an impressive teaching career from 1945 to 1952, first at New York’s New School for Social Research, and then at the London School of Economics. But the Palley we know as an “iconic legend” didn’t really emerge until he set up shop on the Atlantic City Boardwalk in 1957, when he opened an art gallery outside the Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel on the Boardwalk. He called it Objet d’Art Galleries and he specialized in the sale of porcelain figures of animals made by Edward Marshall Boehm (pronounced Beem). This was one instance where Palley didn’t pull any punches. The Boehm figurines were, and are, valuable.

With a sign over the entrance that read, “Merchant to the Rich,” Palley managed to stay in business on the Boardwalk until 1979. The Palley life story, however, began to get really interesting in 1978.

The hope back then was that legalized gambling in Atlantic City would benefit local retailers. It did not, and Palley, who never really sold a lot of merchandise on the Boardwalk, claimed that by the time gambling was legalized, he was in financial trouble. In one of his many written musings, he recalled his next step.

“I bought 27 acres at Park Place and the Boardwalk one year after gambling was voted in in New Jersey,” he recalled. “Not having any money, I bought a $16 million property from eager sellers with $100,000 down and an enormous mortgage due in nine months. Ten days after the papers were signed, I sold the property to Bally, took some of the money, bought a sailboat and sailed around the world for the next 20 years.”

He told that story again and again through the years, and he told it to me in his later years when we met occasionally at social gatherings in Philadelphia. Time Magazine, in a 1978 story, clarified details of the transaction.

“Bally’s leased the fabled Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel for $850,000 a year from Palley and a lawyer named Martin Blatt,” Time reported. Note: Bally’s demolished the grand old hotel in January of 1979.

While there’s no doubt that Palley was one heck of a sailor, his claim of sailing around the world in a sailboat for the next 20 years was another exaggeration, because in 1977, he was named to serve as chairman of the New Jersey State Lottery Commission. But he still wanted to own Boardwalk property.

That August, he partnered with several investors, including New York Jets owner Sonny Werblin, to lease Howard Johnson’s Regency Motor Inn and build a casino. Less than a year later, Werblin dropped out, as the media and area politicians cited a clear conflict of interest. New investors couldn’t be found, and the whole thing fell apart in May of 1978.

Though Palley clearly relished his post as Lottery Commission chairman, he still couldn’t resist inflating his importance, claiming in his memoirs that he “took the lottery’s gross income from $100 million to $1 billion in two years.”

Palley’s maneuvering caught up with him in 1983, when New Jersey Gov. Thomas Kean suspended him from the Lottery Commission. The charge was falsifying documents in a conflict of interest investigation that focused on his dealings with a company doing business with the Lottery Commission. The details were reported in a New York Times piece published on May 1, 1983:

“The indictment follows a civil complaint by the Executive Commission on Ethical Standards charging the Atlantic City businessman and art dealer with soliciting personal business from Syntech International, Inc., a bidder on a contract to provide video lottery games.”

The video idea, which was later scrapped, was Palley’s. But when the ethics panel began an investigation of what Palley was doing with Syntech, Palley started fabricating documents, including an apology for a bill to Syntech for services he performed during a trip to China. Palley said the bill was sent by mistake, but that defense wasn’t enough. Palley was indicted and could have served an 18-month prison term. He caught a break, as Gov. Kean only called for Palley’s resignation.

After his departure from the Lottery Commission, Palley continued sailing, creating what was called, “The Palley Index of Danish Furniture, 1900-2000,” invested in art, wrote several more books, and told more tales. Two of his more fascinating stories involved his opening a sewing machine needle factory in Russia, and how he flew 750 friends to Paris for a weekend on two chartered 747s and ended up making money from the whole thing.

Though it was often difficult to separate truth from fiction when dealing with the long list of Palley’s yarns, there were some quite impressive and verified accomplishments among them. One that stands out was his restoration of San Francisco’s V.C. Morris Gift Shop at 140 Maiden Lane, the only example of a completed Frank Lloyd Wright building in that city. “I left the building as Wright had conceived it,” Palley said at the time.

But his focus through a good portion of his life was Atlantic City. His boasts and eccentricities sometimes overshadowed the fact that he truly loved Atlantic City and wanted it to be the best that it possibly could be.

Unfortunately, in true Palley fashion, some of his opinions were, at the very least, unrealistic and controversial. In 2012, three years before his death at the age of 93, Palley spoke extensively with Paul Mulshine, a reporter for The Newark Star Ledger newspaper.

“Reese Palley thought that Atlantic City should not have people living in it,” Mulshine reported. “He thought it should just be a city of businesses and the people should be moved out of the city. That sort of talk nearly got Palley ridden out of town on a rail. But by 1998, no less a person than Brendan Byrne, the governor who pioneered gambling in Atlantic City, was quoted in this paper as saying Palley ‘had the right concept: Make the island a resort and put the housing on the mainland.’”

When asked how he managed to remain in the public eye – in one way or another – for so long, he told The Philadelphia Inquirer upon his return from one of his famed sailing trips, “It’s not that I’m so exciting,” he said. “It’s just that everybody else is so dull.”

Shortly after his passing, his third wife, artist Marilyn Arnold Palley, could only say, “Reese believed every moment of life is an event.”

And so it was.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.