On Jan. 17, 1920, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, a law that banned “the manufacture, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States,” went into effect several months after it was ratified under the aegis of President Woodrow Wilson. “The Volstead Act,” sponsored by Representative Andrew Volstead, Republican from Minnesota, was more commonly known as Prohibition,

It would last until 1933.

Atlantic City, then and now, was a resort town focused on pleasure; and pleasure, for many visitors during Prohibition, meant alcohol, gambling and prostitution.

Republican powerbroker Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, who knew that such pleasures were matters of supply and demand, ensured that the laws against such things, especially alcohol, were rarely enforced. From 1920 to 1933, Atlantic City was considered to be a “wide open” town. Indeed, whatever was banned by the law was available in Atlantic City during those years.

At the time, Johnson was quoted as saying, “We have whiskey, wine, women, song and slot machines. If the majority of the people didn’t want them they wouldn’t be profitable and they wouldn’t exist.”

While Johnson controlled city and county politicians and law enforcement through bribes, gifts and kickbacks, it was organized crime — national organized crime — that truly held the purse strings on vice in Atlantic City, and on Nucky Johnson himself.

Organized crime was interested in Atlantic City for two reasons: the opportunity to make vast amounts of money by way of making alcohol, gambling and prostitution readily available in a town where there was an incredible demand; and because the city, as a prime beachfront location, was one of the nation’s leading locations for smuggling liquor ashore.

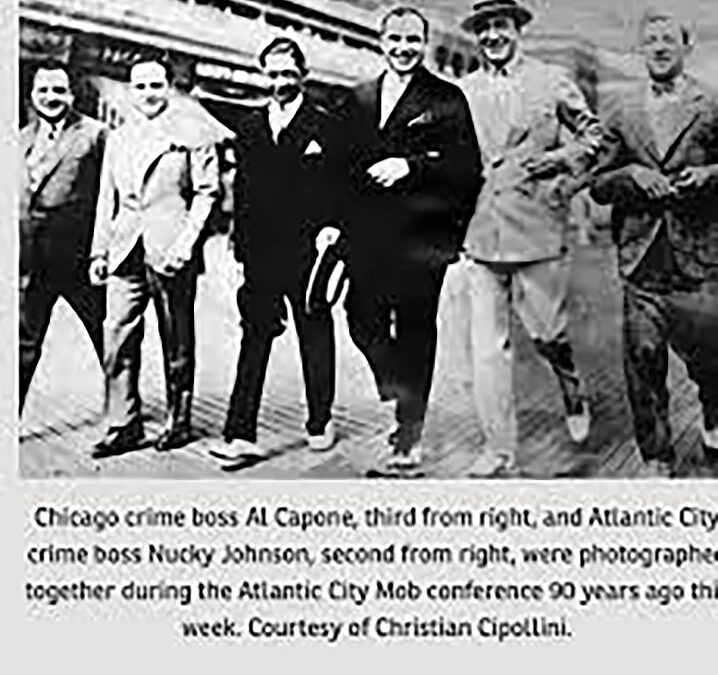

Because of Atlantic City’s importance, from May 13 through May 16 of 1929, Johnson hosted what was later called the “Atlantic City Conference,” held at the Ambassador, Breakers and Ritz-Carlton (the Claridge would be a major mob meeting place shortly after its 1930 opening).

Collectively, the guests in attendance represented nearly every major figure in national organized crime at the time, including Al Capone, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello, Dutch Schultz, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, Moe Dalitz, Albert Anastasia and Vito Genovese — a dangerous bunch to be sure.

There was a lot to discuss, including territorial issues, cutting back on the use of violence, and serious talk about coming together to form one, cooperative, national network. In time, that network would be known as the National Crime Syndicate. The meeting itself, when written about in detail years later, was described as the first true summit of crime bosses in the country.

All of this took place at four Atlantic City hotels. It’s been said that Nucky Johnson’s offices actually comprised an entire floor of the ultra-elegant Ritz Carlton. The Ambassador, built in 1919 with 200 rooms, and expanded with a 500-room addition two years later, was actually built without a bar because of Prohibition. However, like other bigger hotels in Atlantic City during that period, plenty of alcohol found its way into the Ambassador.

By the time the mob visited the Breakers, it had become a 12-story hotel with a 17-story façade facing the Boardwalk. Amenities included a bathhouse, a banquet hall and a rooftop restaurant.

Because of its glamour and opulence, the Claridge was considered to be a safe meeting place for organized crime leaders, who gathered there over the years not only to oversee their extensive, illegal operations, but also to ensure that the flow of alcohol continued to be plentiful. Further, for many years it was rumored that tunnels connected the hotel to the Boardwalk and nearby speakeasies, allowing discreet movement of liquor to Claridge high-rollers. Those tunnels have not yet been found.

It was a wild and lucrative time for Atlantic City. Restaurants, nightspots and other tourist attractions in the city were thriving, which is perhaps the main reason why no one really cared about the rampant corruption at the time.

Other than the hotels, the city had a number of other notorious gathering spots and speakeasies. Three of the more famous clubs were Babette’s, considered to be the most elegant of the city’s restaurants and nightspots. The still-standing Irish Pub was also a big-time speakeasy during Prohibition. The consumption of alcohol at the Irish Pub was so public that the local police had no choice but to raid it, if only for appearances’ sake. No matter. After the raid, the bar moved upstairs.

Also very much with us is the Knife & Fork Inn, only eight years old when Prohibition was passed. What started out as an exclusive, men’s-only club in 1912 became, by 1920, one of the city’s top dining establishments and a place that openly defied the ban on alcohol. The Knife & Fork was also raided, and it’s been said it stopped serving alcohol after the bust, though there was little doubt that if a customer wanted it, alcohol was available.

As the years wore on, support for Prohibition waned. It had proved to be virtually unenforceable; the costs of trying to enforce the law had continued to skyrocket, and organized crime had become more powerful as a result of the unpopular law. To put it simply, people wanted their liquor again.

The Great Depression contributed to the end of Prohibition as well. Indeed, a liquor tax would help fund President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The 21st Amendment to the Constitution, which would repeal the Volstead Act, became law on Dec. 5, 1933.

Though the consumption of alcohol was legalized, other vices, particularly gambling, were not. As one veteran Atlantic City resident once put it, “There was more gambling in this town before it was legalized in the casinos.”

While there was still plenty of corruption in Atlantic City, with the repeal of Prohibition, Nucky Johnson lost a good deal of his income and power. In 1939, he was convicted of tax evasion, and in 1941, he was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison and fined $20,000. He served four years and upon his release, worked in sales for the Renault Winery and the Richfield Oil Company.

Though he died on Dec. 9, 1968, the legacy of Nucky Johnson, and the Prohibition era in Atlantic City, were immortalized by author Nelson Johnson (no relation) in his 2002 book, “Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times and Corruption of Atlantic City,” and in the groundbreaking 2010 HBO television series, based on the book.

Some legends never die. They just end up on TV.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.