By Bruce Klauber

Tibor Rudus was a Hungarian entrepreneur who thought big. Very big.

Born in Budapest in 1920, he performed as a soprano in the Budapest Opera at the age of 8. He also trained as an acrobat with his twin brother, Andras. The two performed an acrobatic act as the Rudas Twins until their careers were interrupted by World War II, when the brothers were imprisoned by the Nazis in the Bergen Belsen concentration camp.

After the war he resumed his career as an acrobat via the formation of a dance act called Sugar Baba and the Rudas Twins. Sugar Baba was Rudas’ first wife, Anna.

When that act ran its course, Anna and Tibor moved to Australia, opened a dance studio, and formed a dance troupe called the Rudas Acro Dancers. The actual act was a French-styled revue based on the famed Ziegfeld Follies.

In the early 1960s, Rudas realized that the money and the opportunities for that kind of act were in the United States, specifically Las Vegas.

Vegas at the time was experimenting with revue shows that were, at least in part, similar to what the Rudas Acro Dancers were doing. In 1963, he hooked up with the Tropicana in Las Vegas.

While in Vegas, he expanded the concept of the dance revue show by adding comics, magicians, jugglers, and other variety acts to the mix. The shows were popular, well-attended, entertaining, and made economic sense. Additionally, the casino and the producers didn’t have to worry about name headliners who might be unreliable or questionable draws. Examples? Remember that Elvis bombed in his first Vegas appearance in 1956, and Judy Garland was notorious for canceling her shows due to illness.

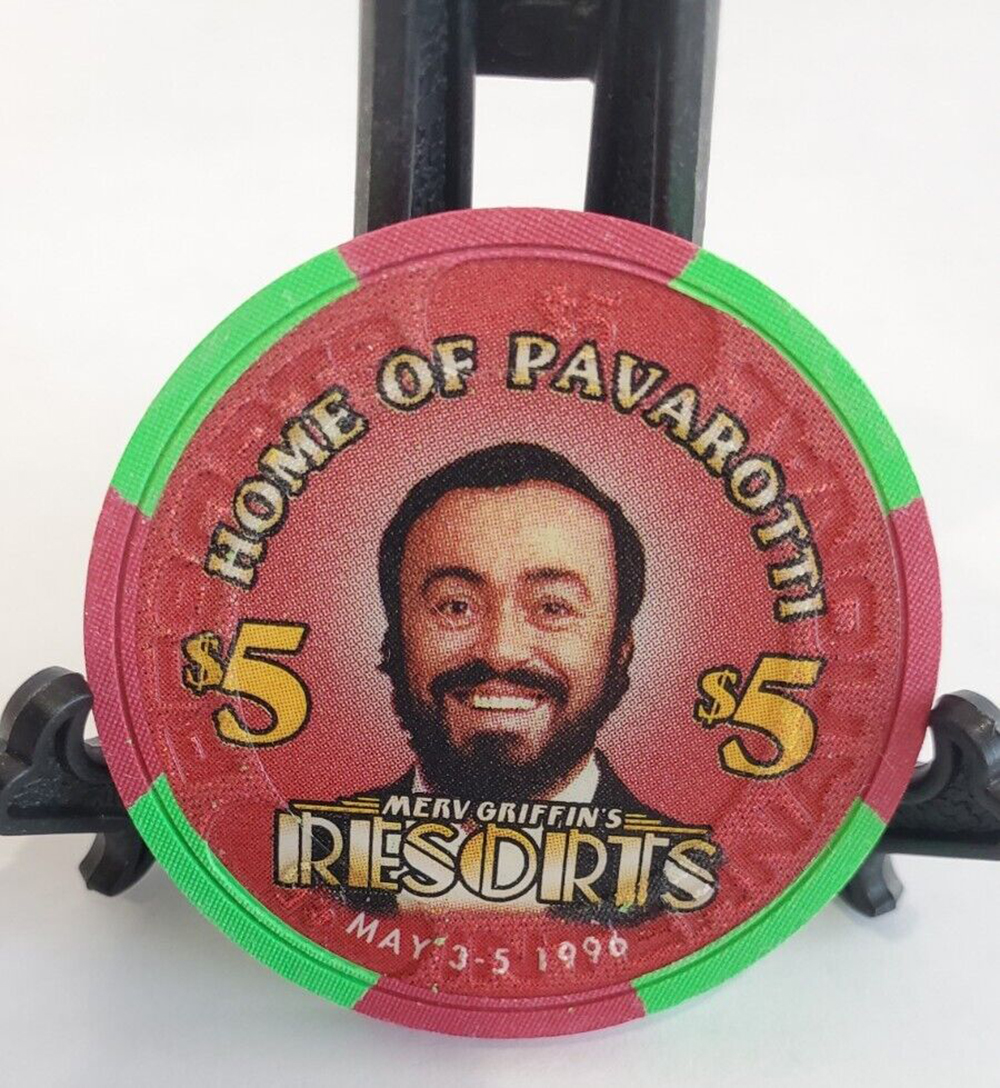

The Pavoratti performance was such a big deal, that they had a commemorative casino chip made to mark the occasion.

By 1967, in addition to what he was doing in Las Vegas, Rudas was producing three shows for the Resorts Casino and Hotel on Paradise Island in the Bahamas. Given his history of innovation, life-long interest in classical music, and his close association with Resorts, Rudas convinced Resorts management in Atlantic City to present classical music programs for the first time. Indeed in the late 1970s, the New York Philharmonic, Joan Sutherland, and Itzhak Perlman all graced the stage of the Superstar Theatre at Resorts International.

“I convinced performers that their talent belonged to a much wider audience,” he told The Times of London years later. “In my variety days, I’d seen classical orchestras perform in casinos in many European cities. People came in droves. When I introduced the New York Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta to the casino showroom, it was the first time such a thing had been dreamt of in America.”

For Rudas, the next logical step, if he could pull it off, would be a real coup: Bring Luciano Pavoratti to the Resorts stage.

In October, 1983, he convinced Pavarotti to come to Atlantic City, but there was one major issue. The tenor, like pop music stars Bing Crosby and Doris Day, simply refused to perform in a casino. Rudas’ solution was to erect a 50,000-square-foot, five-story-high tent on an empty lot adjoining Resorts. Not only did that work for Pavorotti, but 5,000 tickets sold out in three hours, which forced Rudas to commission an even bigger tent with amenities to be approved by Pavarotti. The final version of the tent was heated, outfitted with 50,000 square feet of carpeting, and a $50,000 lighting system was installed. A sound engineering expert was brought in from London to work with Pavarotti on the acoustics.

According to United Press International, on Oct. 29, 1983, “Luciano Pavarotti brought opera to the boardwalk, drawing a standing room only crowd of more than 7,500, high-rolling gamblers and classical music buffs to a concert held in a tent at an Atlantic City casino. The burly, bearded Italian superstar was greeted with wild applause and cheers as he sauntered through the orchestra, the 87-piece New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, and walked to center stage. Clutching his familiar white handkerchief, Pavarotti sailed through the first of seven arias by Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gaetano Donizetti, drawing ‘bravos’ from the crowd.

“Officials at Resorts International Hotel-Casino, who hoped Pavarotti’s appearance would help them recapture their reputation for top-flight entertainment after stars like Frank Sinatra and Diana Ross went elsewhere, said Pavarotti had created an unprecedented stir in the gambling resort.”

Resorts’ PR chief Phil Wechsler said at the time, “There isn’t a room to be had in town this weekend. We could have sold triple the number of tickets we did.”

Pavarotti, who arrived Friday night in time to attend a lavish private party for dozens of premium players flown in by the casino for the concert, said his performance represented a new frontier for music. “When you do something new, people are always skeptical,” he said. “But the reason I am performing here is to bring opera to more people.”

On Oct. 29, 1983, Luciano Pavarotti came to Atlantic City drawing a standing-room-only crowd of more than 7,500 to a tent outside of Resorts.

The unprecedented success of the event led to Rudas’ departure from Resorts to produce Pavarotti’s concerts all over the world. That included a booking at Atlantic City’s Taj Mahal in February of 2003. He later presented The Three Tenors (Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo and José Carreras) internationally.

Rudas, who died in September of 2014 at the age 94, was proud of his accomplishments, despite the skeptics and the critics. “I am the bad boy who took opera out of the opera houses and gave it to the masses,” he told The Philadelphia Inquirer in his later years.

That was quite an accomplishment, and it hasn’t been done in Atlantic City since.