Sarah Callazzo, 27, speaks with a clarity that comes from surviving something heavy and choosing to turn that pain outward into purpose. As the founder of Love, a Stranger, a newly launched national support line for people affected by eating disorders, she is building something rare: a space that meets people exactly where they are, without judgment, without shame, and without the pressure to be “sick enough” to deserve help.

“People struggling with eating disorders often don’t feel worthy of support,” she says. “I know what that feels like. I’ve been there. And I never want anyone to feel like they’re fighting alone.”

Love, a Stranger is her answer to that loneliness.

The journey that led to a movement

Callazzo grew up as a competitive dancer in Toms River, a world where perfection was treated as both discipline and identity. By high school, disordered eating had crept into her life. In college—despite excellent grades, leadership roles, and a carefully maintained image of composure—her symptoms escalated.

“I was doing everything right on paper,” she says. “But I was really struggling inside.”

Like many with eating disorders, she convinced herself she didn’t qualify for help. “I had friends who had been hospitalized. In my mind, they were ‘sick enough.’ I wasn’t,” she recalls.

Everything shifted in 2019 when she admitted to herself that something was deeply wrong. “Recovery wasn’t a magical moment. It was a choice I had to make every single day. And even my hardest day in recovery was better than my best day with an eating disorder.”

Through reflection, and connection with others in recovery, Callazzo discovered not only her own strength but a pressing need for broader, more accessible support—especially in moments when people feel most isolated.

Advocating on college campuses and within greek life

Before launching Love, a Stranger, Sarah Callazzo’s advocacy found its home on college campuses, where she spoke to thousands of students about the realities of disordered eating. After joining a national speaking agency, she traveled to universities across the country—Stockton, Pittsburgh, campuses in California and New England—sharing her story with a level of honesty she once never believed possible.

Her most impactful work, she says, has been within Greek life communities, where pressures around image, social hierarchy, and belonging can quietly fuel disordered eating. Callazzo, a former sorority president herself, understands the culture from the inside.

“Eating disorders don’t start on college campuses,” she says. “But college is where the cracks widen. In Greek life especially, everything feels magnified—your appearance, your social value, the pressure to be ‘on’ all the time.”

Her presentations strip away the polished facade associated with Greek life and replace it with vulnerability. She speaks candidly about restrictive dieting, binge-purge cycles, compulsive exercise, ritualized body comparisons, and the quiet, normalized ways students harm themselves without calling it an eating disorder.

“I walk into a chapter house and say, ‘I was sitting exactly where you are,’” she explains. “‘I know what choices you think you’re making. I know the things you normalize.’”

Her goal is not to shame or lecture but to open a door—to give students permission to acknowledge their struggles and seek help.

The moment everything changed

The seed for Love, a Stranger was planted during a national controversy. When the National Eating Disorders Association shut down its longtime helpline and replaced it with an AI chatbot—one that infamously advised a young person to “eat a salad and go for a walk”—Callazzo was stunned.

“I couldn’t believe it. Suddenly, there was no real-time text line anywhere in the country for people struggling with eating disorders,” she says. “That blew my mind.”

At the time, she was finishing her master’s degree in social work at Rutgers. She kept coming back to the same thought: “Someone needs to fix this. Why not me? Why not now?”

What followed were months of behind-the-scenes labor—software systems, liability and risk management, volunteer training, protocols, safety infrastructure. “It was the least glamorous work on the planet,” she laughs. “But I wanted to make sure it was done right. People deserve a safe, thoughtful system.”

On November 10, her birthday, Love, a Stranger officially launched.

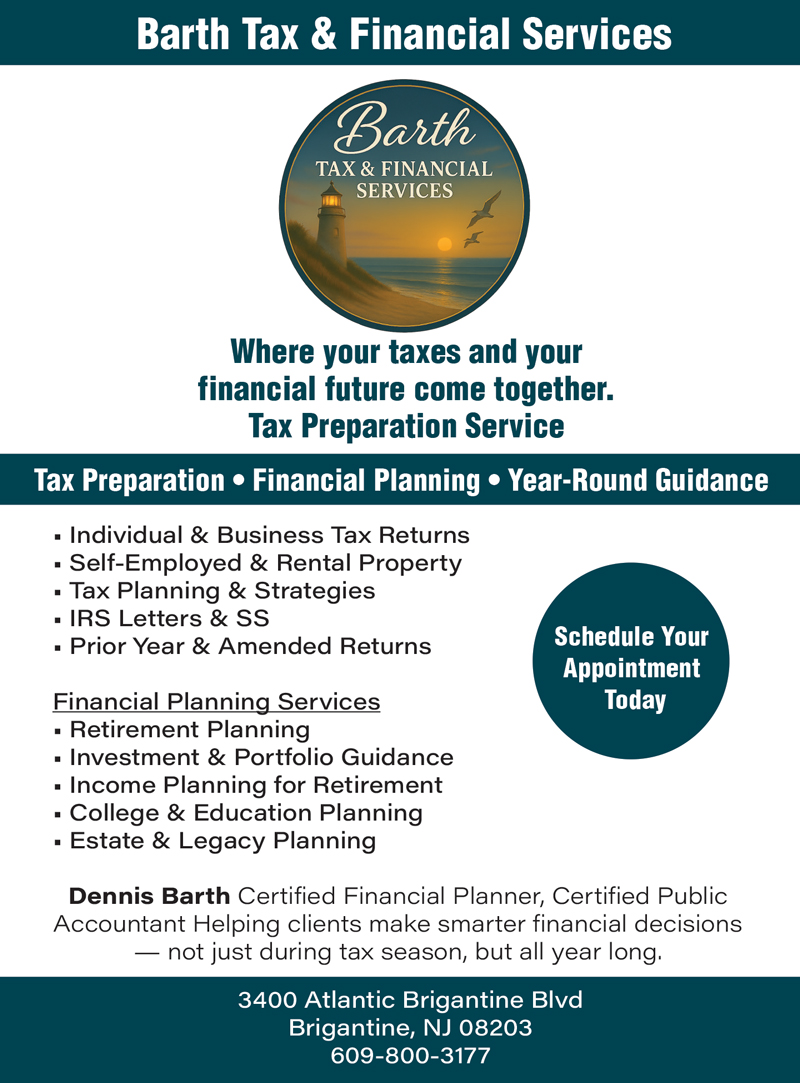

How the helpline works

Love, a Stranger is not a clinical service and not a crisis hotline. Instead, it offers something both simpler and profoundly necessary: human connection.

Anyone—whether a person with an eating disorder or a supporting family member—can text 601-348-LOVE (5683) to reach a trained volunteer who will listen, validate, and offer guidance or resources.

“Maybe you’re at a restaurant and your friends are talking about diets,” Callazzo explains. “Maybe you’re scared of the menu. Maybe you’re a parent and don’t know what signs to look for. You can text us. It’s discreet. It’s immediate. And you don’t have to explain your whole life story.”

Volunteers for Love, a Stranger are located across the United States—from New Jersey to California, Maine to Florida—and receive extensive training before supporting callers.

The goal is to make support accessible in moments when people are most vulnerable.

“So many people spiral alone in their bedrooms,” Callazzo says. “So many parents have no idea what they’re seeing. We want to be the person on the other side of the phone who says, ‘You’re not crazy. You’re not alone. Let’s walk through this together.’”

Within a month of launching, the line received inquiries from nine different states, despite minimal publicity.

“It was important for us to help out during the holiday season, because it can be a triggering time for people struggling with eating disorders,” Callazzo explains.

The name that says everything

“Love, a stranger” came from two moments in Callazzo’s past.

First, from the nature of eating disorders themselves: isolating, often hidden, rarely understood. Strangers—teachers, roommates, coworkers—often notice the signs before loved ones do.

Second, from a project in which Callazzo wrote 300 anonymous encouragement letters to people receiving inpatient treatment for eating disorders. She signed each one: “Love, a stranger.”

The author behind the advocate

Before founding Love, a Stranger, Callazzo told her story through a different medium: her book, Unknown Warrior: Battling the Mirror.

The title came from a poet who, on Thanksgiving years ago, typed a spontaneous haiku for her at a market. The words “unknown warrior” struck her deeply.

“They captured something I couldn’t put into words,” she says. “When you’re battling an eating disorder, you feel like you’re fighting an invisible war.”

Her book mirrors the nonlinear nature of recovery. One page might contain a poem; another, a candid admission; another, a single sentence: You’re a bad bitch. Don’t let anybody tell you otherwise.

“It’s messy on purpose,” she explains. “Recovery is messy.”

Advice for families, and for those struggling

For loved ones supporting someone with an eating disorder, Callazzo offers three core pieces of guidance: Education, Compassion, and Flexibility.

And to anyone facing an eating disorder themselves, she shares a message she wishes she had heard sooner: “What you look like is the least interesting thing about you. And if your eating disorder is getting louder, it’s because it knows it’s losing. There is light ahead, even if you can’t see it right now.”

“If you’re reading this and something feels off, you deserve help,” she says. “You deserve a life you love, in a body you love. And you don’t have to walk out of the darkness alone. We’re here. Just reach out.”