The Casino File

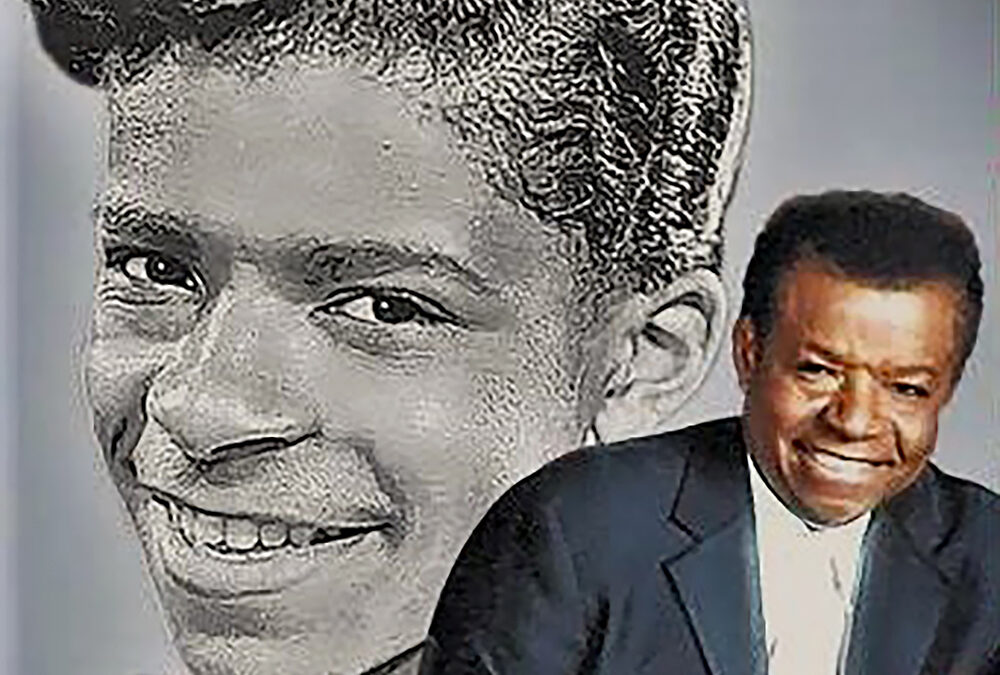

The reason cliches become cliches is because they are grounded in truth. For instance, one of pop music’s most ingrained tropes is that of groups of 1950s urban youths gathering in subway stations, school bathrooms or other, similarly tiled spaces in order to enhance the sound of their vocalizing. But that’s exactly how one of pop music’s most venerable performers, “Little” Anthony Gourdine, launched his still-thriving career in the 1950s.

Gourdine, 84, recalled his show business beginnings during a recent phone chat in advance of the June 13 appearance by his legendary vocal group, Little Anthony & The Imperials, at Ocean Casino Resort. They’re part of the “Happy Together” package tour that also includes The Turtles, Jay & The Americans, Gary Puckett & The Union Gap, The Vogues and The Cowsills.

During the conversation, the still-spry-and-loquacious Gourdine reflected on his earliest days as a performer harmonizing for commuters and fellow high school students in his native New York City.

“We got together at a place called the Hoyt–Schermerhorn [station] in Brooklyn,” he recalled. “All of the trains of New York, Queens, Brooklyn, they all met at this one place, so you could change to another train to get to wherever you were going.

“So, we would get all these [students] all coming at the same time and transferring to go to their [schools and homes]. We had a built-in audience of all these teenagers and the adults, the people that were on the subway. We would sing and draw great crowds, especially when we were doing well and you knew you were doing something they liked.”

However, he continued, he and his pals missed a lucrative opportunity out of naivete and inexperience.

“We didn’t know that if we put a bowl or something down there, people would put money in it,” he lamented. “If we knew that, we would’ve made some money.”

Not that monetary rewards were the motivation for him and his harmonizing pals. “We did it for fun because there was an echo down there,” explained Gourdine. “No one I remember ever said, ‘I’m gonna be a big star.’ The driving force was our art form. What we were doing, and competing with one another, was really where the excitement and the passion was.”

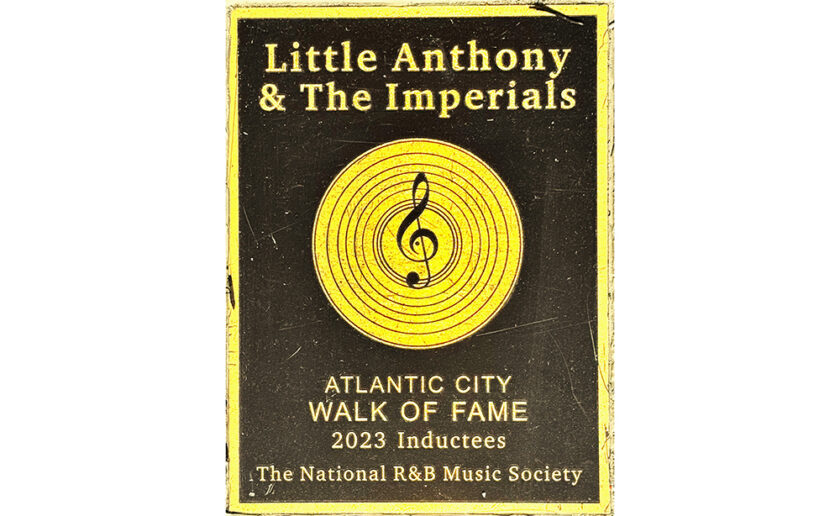

Whether or not stardom was a goal, it was obviously in the cards for Gourdine, whose clarion falsetto would be the trademark on such signature tracks as “Shimmy, Shimmy, Ko-Ko-Bop,” “Going Out of My Head” and, of course, 1958’s “Tears on My Pillow,” which ignited the career of Little Anthony & The Imperials (whose original name was The Chesters) — a career that led to the unit’s 2009 induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (they are also honored with a National R&B Society plaque embedded in Brighton Park between the Boardwalk and Claridge Hotel).

Battling Jim Crow

Today, touring African American artists are limited only by their budgets when it comes to traveling. But that certainly wasn’t the case during Gourdine’s early years as a recording star and concert attraction; the late-1950s and early-‘60s were a time of legal segregation in southern states.

“It was very bad,” he offered. “I had a heads-up because all of my mother’s side of the family and my father’s were all southerners. My mom was from Savannah, Ga., and my dad was from Charleston, SC. They would tell me it ain’t the same up in the big cities of the north as it is down there. But you really didn’t know until you actually experienced it.

“A lot of days, I hear people say, ‘This one’s a racist; that one’s a racist,’ he continued. “You don’t even know what a racist is no more. We lived it. We were there. We felt this thing of Jim Crow.

“When I got to Richmond, Va. [in 1958], we couldn’t stay in a regular hotel. I’m a kid that’s been, you know, protected by my mom and my dad, especially my mom, and all of a sudden, I’m on my own and I’m in some seedy little hotel on the other side of the tracks.

“I was very lonely. It was Christmas Eve, and it was the worst time of my life, which was supposed to be the most fun time of my life, singing and performing on stage.

“Once you got out there on the stage and you sang and performed, that moment was wonderful. Then, you have to come off the stage. And in the South, in the places where Jim Crow segregation was so strong, they could actually applaud you when you’re singing, and then when you get off, they’re ready to lynch you.”

His most dramatic recollection is of a gig in Birmingham, Ala., where the theater was divided into seating sections for white and Black patrons with the Black section located behind the stage.

“I was on the tour with LaVerne Baker and Bo Diddley and a bunch of other people, and they were trying to teach me: ‘Hey man, just sing to the white folks,’” he recounted. “ But I say, ‘Why?’ I’m from Brooklyn, so I don’t see it that way. All them people paid their money; I got my back to them. That doesn’t seem right.’ I actually ordered the group we were gonna sing to the wall, to the wings, so each side will get half of us.

“It made the [white concert] promoters so incensed that we had to rush to our bus because we were told that a white-supremacy group was gonna shoot the bus up.”

Things were so bad that Gourdine, whose first name is Jerome, entertained thoughts of leaving show business. But his mother would have none of it.

“I actually called my mother,” he remembered. “I said, I was gonna leave the tour; I wasn’t gonna stay anymore in that world. I was ready to book me a flight and come home to Brooklyn where I knew everybody, where everything made sense.

“And my mother said, ‘You stick with it. You don’t quit.’ So, I got that exposure to it. Not once, but many, many times over the years.

“I watched the Civil Rights movement grow and grow and grow, and things began to disappear. A lot of people sacrificed their lives for that. But what people call racism today [is erroneous] because they don’t know what they’re talking about. Really. It’s so stupid.”

While those experiences were obviously profound, Gourdine came out of that time less-scarred than many of his contemporaries.

“A lot of people — I won’t name names — are very bitter,” he said. “[Time couldn’t] erase these feelings of dejection and rejection simply because of the color of the skin. But I was a blessed man; there were so many wonderful people that came into my life and just kind of made me think a little differently.”

One person with whom he shared his feelings back then was Smokey Robinson. “We talked about it. We weren’t bitter at all. We were angry at first, but we weren’t bitter.

“We understood. We were told, that’s the way it is. And so you learn from that. It’s a learning process of human nature. But you start learning everybody’s not bad. Even in the South.

“I think about it often, and I say I grew from it more than anything. I’m very blessed in that way. I had a mother and father who were very, very strong faith people. They taught me that in the end, it was about the God that loved me. And it really wasn’t about anything else.

“And so, I didn’t have any hate. To this day, I’m not mad at nobody.”

For tickets, go to ticketmaster.com.

Chuck Darrow has spent more than 40 years writing about Atlantic City casinos.