Joan Myers Brown, founder of the famed and iconic Philadanco Dance Company, is an international treasure.

This ageless force of nature – she’s happy to admit to being 93 – has won just about every award there is to win; and Philadanco’s substantial contributions to dance, arts and culture have been acknowledged all over the world.

Just some of those awards include the 2012 National Medal of Arts, presented to Brown by President Barack Obama; the Philadelphia Award; honorary doctorates from Ursinus College and the University of Pennsylvania, the American Dance Guild Honoree Award and The Philadelphia Inquirer’s 2017 Industry Icon Award.

But before she founded The Philadelphia School of Dance Arts in 1960 and Philadanco 10 years later, Joan Brown was a professional dancer. One of her first major jobs, and the one that helped launch her career, happened in Atlantic City’s Club Harlem.

A native Philadelphian and West Philadelphia High School graduate, the young Brown began her journey into the world of dance courtesy of her gym teacher, who suggested that she join the ballet club and take private lessons. What made Brown’s start so unique is that she was Black and her first teachers were white.

“In the 1940s and 1950s, ballet schools throughout America were segregated,” Brown explained to Suzi Nash of the Philadelphia Gay News. “If you lived in Philadelphia and were Black, you were not permitted to try on shoes in a store and you were barred from the white ballet schools.”

From there she studied with Sydney King and Marion Cuyjet, two Black ballet teachers, which led to a scholarship that allowed her to study both ballet and the Katherine Dunham technique in New York at the Dunham School. Not long after, she took a class for a year with the English-born Antony Tudor when he came to teach for the Philadelphia Ballet Guild. That was the first desegregated ballet class in the city.

While in the city, she danced in recitals, the Philadelphia Cotillion Balls, and the local Black cabaret circuit, then in clubs throughout the country.

An early highlight for Brown was her appearance in the corps of “Les Sylphides,” staged for a performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

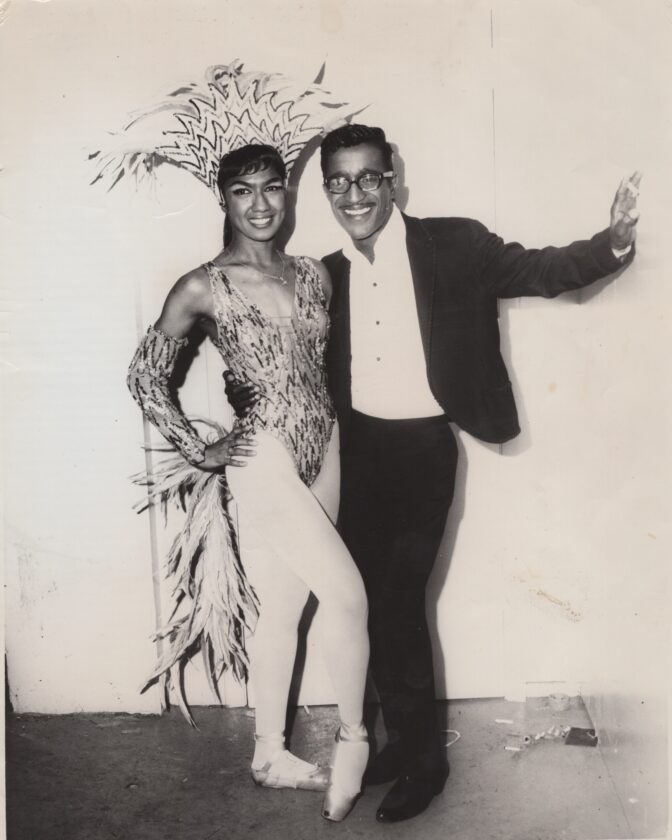

Despite how impressive her early resume was, a living still had to be made. And by 1958 she was making a living by dancing at Atlantic City’s Club Harlem as a part of the popular Larry Steele “Smart Affairs” revue as “featured ballerina en pointe,” and as choreographer. Some of the performers she backed as a part of Steele’s revue included Sammy Davis Jr., Cab Calloway and Pearl Bailey.

Brown formed a particularly strong bond with Bailey.

“I worked with Pearl Bailey on and off for two years, beginning around 1958,” Brown told me in a recent conversation. “She saw me dance at Club Harlem and hired me to dance in her show. At that time, Atlantic City was segregated, and Pearl was working in a club on the white side of town. I was working on the Black side of town. After her show, she came into Club Harlem. As for Pearl, she fluctuated. Sometimes she was an SOB and sometimes she was a sweetheart. It was according to how she felt that day. She fired me one day – she thought I was cursing – and before I could get back home to Philly, she had the company manager called me to come back.”

The work was hard and not pleasant all the time.

“Some places you had to mix,” Brown explained. “After the show you had to sit at the bar and socialize with the patrons. I wasn’t a drinker, so I didn’t care for it. I’d stay in the dressing room or hide in the bathroom. That’s one time when segregation actually helped me.

“Because in places like Atlantic City, or Las Vegas, when I was with Pearl, I was the only Black girl in the show, and I wasn’t allowed in the clubs. So the white girls had to mix and I got to go home!”

Eventually realizing that as a Black ballet dancer she would never find work in a classical ballet company, she decided to open the Philadelphia School of Dance Arts as a way to start addressing that issue.

“In 1960, I was still dancing,” she recalled. “I was performing and choreographing shows, mostly at Club Harlem. I taught ballet in the afternoon and shuffled off to Atlantic City every night.

“The hardest part was the commute those first six years. I went to sleep at the wheel one night, and after that, my boyfriend at the time was nice enough to drive me back and forth, or I’d ride the bus.”

Joan Myers Brown was determined.

In 1970 she made the decision to create new opportunities by forming Philadanco. She started with 30 students. With time came community recognition and visibility, as did Brown’s realization that the dancers in the school would likely face the same challenges she did with performance opportunities.

Now a Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts resident company, and an internationally renowned company that sells out venues all over the world, Philadanco’s influence continues to be pervasive.

Just ask some of Philadanco’s distinguished alumni, including Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater choreographer Hope Boykin, Tony Award winner Leslie Odom Jr. and Willia Noel Montague of Broadway’s “The Lion King.”

“Philadanco has truly made me into the artist and woman I am today,” Noel said. “Joan Myers Brown’s loving instruction not only nurtured my skills as an artist, but also taught me the invaluable lesson that you are only as good as your last performance. Whenever I step on stage, I find a new energy and meaning for the gift of dance, and I owe much of my success to my Philadanco family.”

Certainly, Philadanco is unique because of its racial makeup, but that’s not why the company is revered and sells out concerts all over the world. A recent review of a Philadanco performance at Bucknell University illustrates why this company is so special.

“Philadanco stunned the audience with their captivating ability to tell stories through movement,” wrote reviewer Rachel Johnston for Bucknell’s Performing Arts website. “The choreography was astounding and perfected, leaving the audience members to murmur their awe. Their ability to effectively convey different stories and passion made their performance truly one of a kind.”

In 2020, after 50 years at the helm of Philadanco, Joan Myers Brown announced her intention to “step away” from her role as artistic director, handing those reins to long-time Assistant Artistic Director Kim Bears-Bailey.

Brown, naturally, will always hold the title of “founder,” and those who know this miraculous dynamo are not surprised that she continues in action on Philadanco’s behalf on a daily basis. As The Philadelphia Inquirer recently said, “The buck still stops with Brown.”

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.