There’s an old show business adage that says casino lounges are either for performers on their way up, or on their way down. There was a time in Las Vegas and Atlantic City when that was true.

Comics Don Rickles and Shecky Green first worked the Vegas lounges, then graduated to the hotel/casino main stages, as did the musical duo of Louis Prima and Keely Smith, and a multi-talented artist who first worked in Vegas at the Fremont Hotel when he was a teenager, and ultimately became known as “Mr. Las Vegas.” That performer was Wayne Newton.

The reverse – headliners who became lounge acts – had little or nothing to do with talent. Changing public tastes, visibility, record sales, and a fickle public, among many other factors, have all contributed to many big names dwindling in popularity. Though these performers still had a name, and still had a following, the name and the following just were not enough to fill a big room.

Three Atlantic City cases in point were singers Johnnie Ray, Billy Eckstine and Julius La Rosa.

Ray, often cited as one of the forerunners of rock ‘n’ roll, burst on the scene in 1952 with his multi-million-selling “Cry,” and “The Little White Cloud that Cried.”

His in-person histrionics – falling on the floor, tearing at his hair, and at times actually crying – were as much an attraction as his songs; at the time, his onstage antics were considered to be outrageous. Of course, that onstage behavior became a given for early rockers a few years later.

Ray not only knocked middle-of-the-roaders like Perry Como off the charts, but “The Prince of Wails,” as he was known, also had a vast younger audience, much like Frank Sinatra had during the mid-1940s bobby-sox era. His 1955 appearance at the Steel Pier was reportedly mobbed.

Some hits followed, but by 1957, his star was dimming, and he was beset by personal problems, though he continued to have an immense following overseas.

In 1981 he started performing with a trio rather than a large orchestra, and it was in that format that he came to Elaine’s Lounge at the Boardwalk’s Golden Nugget. While in town, he also participated in the filming of a television pilot at Resorts International, hosted by game show maven Bob Eubanks. It received little distribution.

He made one more appearance at the Jersey Shore before his passing in 1990. He headlined at Cozy Morley’s Club Avalon in Wildwood in 1987. A blogger named Bill Janovitz was there. “He was already 60, but his voice was huge,” he recalled. Johnnie Ray died in 1990 at age 63.

Vocalist Billy Eckstine was a pioneering bandleader whose mid-1940s bebop orchestra had, among others, bop pioneers Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie as members.

The romantic baritone known as “the sepia Sinatra” was tremendously popular in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and in 1951, was the first African-American artist to headline at the Steel Pier.

A controversial photo taken for Life magazine not long before that depicted Eckstine surrounded by a group of admiring white female fans. It caused such an uproar that, said pianist Billy Taylor, it “just slammed the door shut for him.” Eckstine’s latter-day appearances were mostly in the lounge of the Four Queens in Las Vegas, and in the mid-1980s, at Elaine’s in Atlantic City.

I encountered him several times during those days. History had sadly passed him by. His once silky smooth, romantic baritone was taken over by a wide vibrato, and he was clearly not a happy man. Billy Eckstine died in 1993 at age 78.

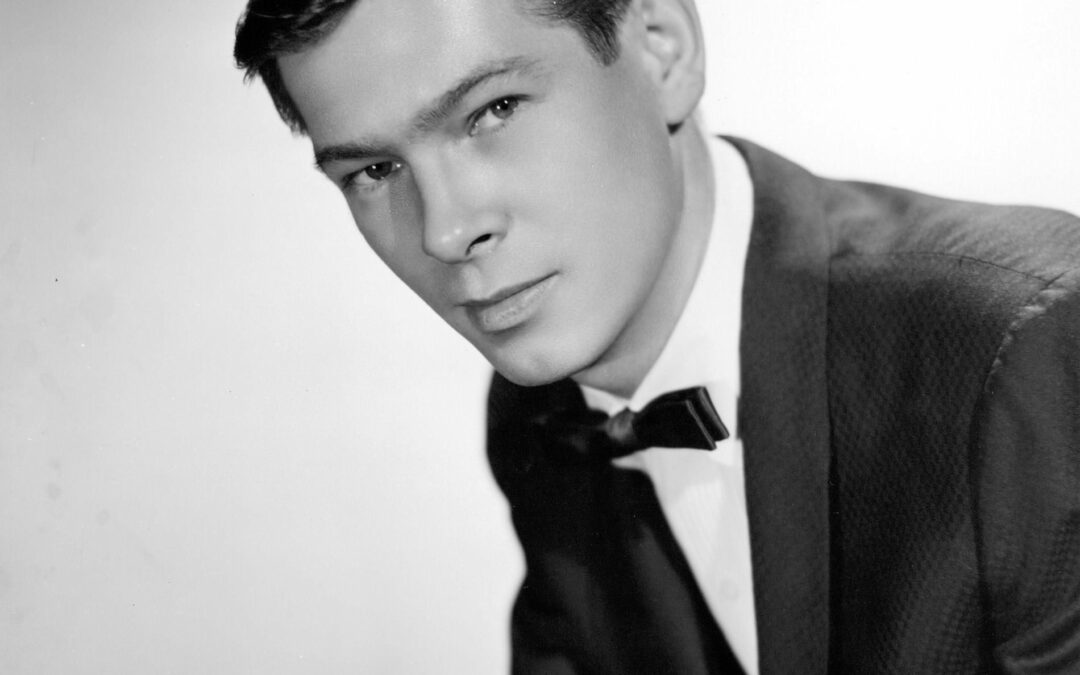

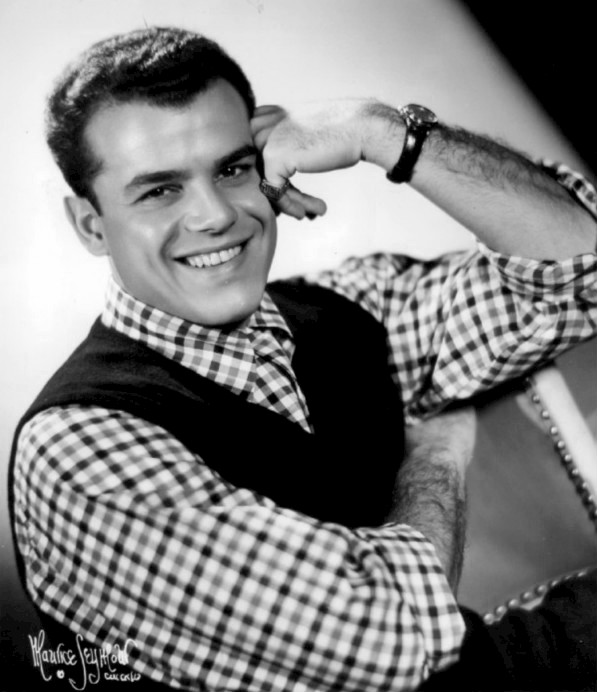

Long before the phrase, “you’re fired,” took on its present connotation, those words were most closely associated with singer Julius La Rosa.

In 1953, young Julie was among a talented cast of characters that populated the top-rated television shows hosted by Arthur Godfrey, “Arthur Godfrey Time” and “Arthur Godfrey and His Friends.”

La Rosa was talented, good-looking, and charismatic enough to garner a load of fans. It’s been said that only a year after Godfrey hired him, La Rosa was receiving 7,000 fan letters a week.

That, and the fact that he hired his own agent, were too much for Godfrey, who had an ego the size of Mount Rushmore. On the morning of Oct. 19, 1953, La Rosa sang “Manhattan” on the Godfrey show. Unexpectedly, Godfrey fired La Rosa on the air, saying that La Rosa had “become his own star,” and “that was Julie’s swan song with us.”

The firing made national headlines, and it didn’t help Godfrey’s case or popularity when he said the reason for the firing was that La Rosa “lacked humility.” Godfrey’s career was never the same after that, nor was La Rosa’s.

Sure, Julius La Rosa was talented, but that unexpected notoriety, which followed him around for the rest of his life, quickly thrust him into the international spotlight. He was all over television, booked in the nation’s best rooms and even made a film or two. He performed several times at the Steel Pier, including a sold-out Labor Day weekend series of shows from Aug. 28 to Sept. 4, 1955.

Though the Godfrey albatross followed him for the rest of his career – “of course that’s what interviewers are going to ask me,” he once told me – he made peace with Godfrey and the incident, and though his star was never what it was in the 1950s, he had a decent and comfortable career that brought him to the lounge at Caesars in Atlantic City in the mid-1980s.

Julie, who passed in 2016 at age 86, was one of my closest friends in show business and among the most literate people I’ve ever met, in or out of the business. In his later years, he turned his attention to writing, and not surprisingly, he was darn good at it.

This was a truly nice man who had become comfortable with his lot and was glad that he was still singing in front of audiences who still wanted to see him, even if it was at the lounge at Caesars. He gave it everything he had, no matter where he was. That’s show business.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.