By Bruce Klauber

As the Jewish people celebrate the High Holidays, this seemed an appropriate time to detail the long and unique association the Jews have had with Atlantic City.

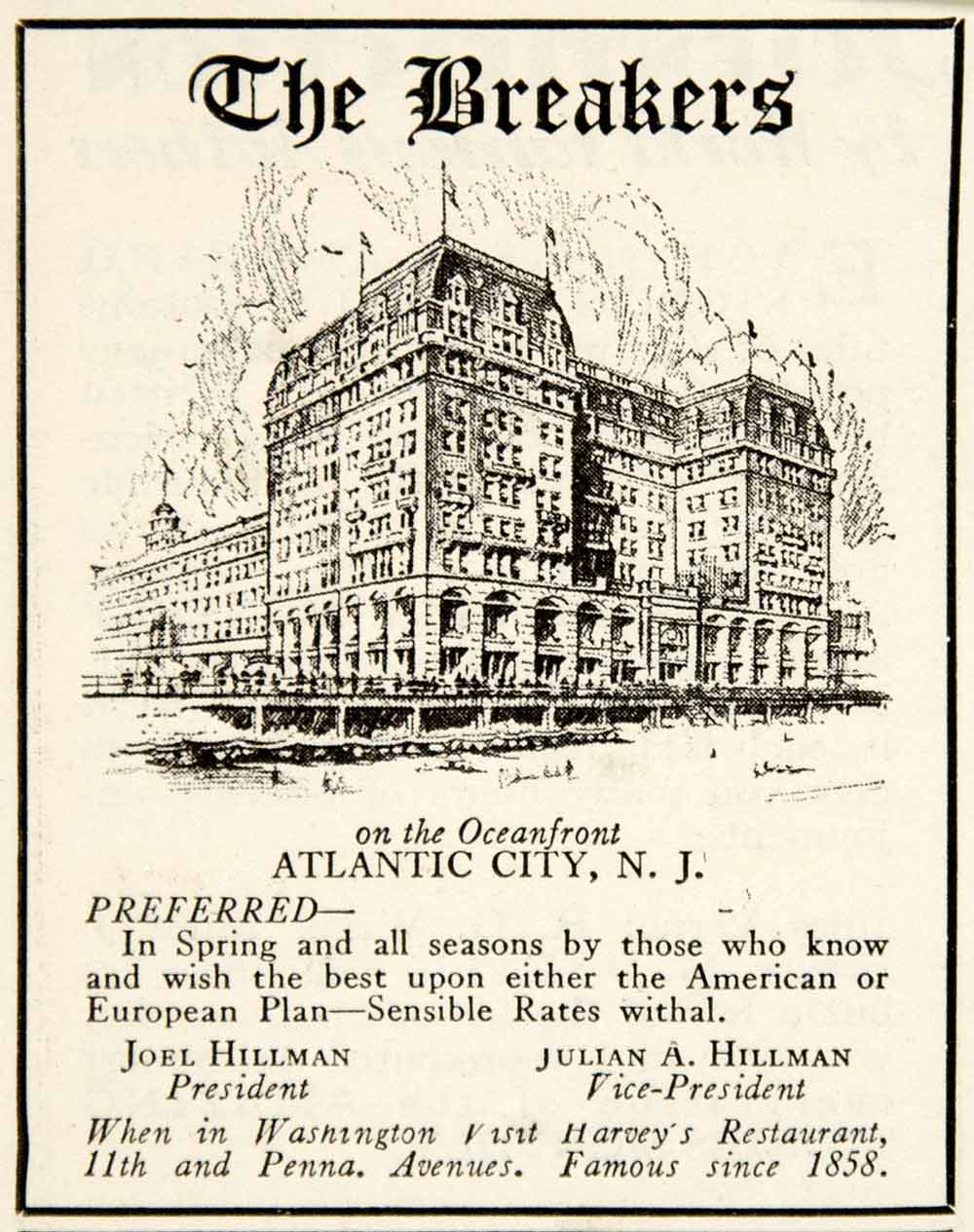

What led me to explore this were my distinct memories of families, including my own cousins, spending Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and sometimes the Passover holiday, at kosher hotels like The Breakers or Teplitzky’s. What I discovered was eye-opening and went way beyond just celebrating Jewish holidays.

According to research published in Hadassah Magazine, “The first High Holiday service was held in a private residence in Atlantic City in 1888, followed in 1893 by the establishment of the first synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel, a Reform community on Pennsylvania Avenue. The first kosher hotel, the Rosenaur Villa, and the Orthodox Rodef Shalom synagogue (still in operation at 4609 Atlantic Ave.) both opened in 1896.”

By mid-century, 10,000 Jews had settled in Atlantic City permanently, which accounted for about a sixth of the city’s total year-round population. Hundreds of small kosher hotels, and even kosher restaurants in private homes like Zawid’s on Kingston Avenue, accommodated the large number of summer visitors.

“So many Jews converged on Atlantic City,” the magazine reported, “that some hotels began restricting their clientele, causing an uncomfortable period of discrimination, but an upsurge in Jewish hotels. During World War II, the city served as a training site for military recruits and a recovery and rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers. The 400,000 soldiers it hosted over a three-year period trained on the boardwalk and were treated at a local hospital. Jewish troops were invited for High Holiday meals.”

Advertisements for Atlantic City hotels began appearing in Jewish newspapers as early as 1885, according to an article in The Jewish Encyclopedia of Western PA. “The Hotel Isleworth (a long-forgotten kosher hotel on Virginia Avenue) was advertising its salt baths, open grate fires and electric lights. Other hotels followed. By the turn of the century, the southern New Jersey coast was a premier destination for well-to-do families.

“The Jewish community of Atlantic City was growing, too, making it a draw for national institutions. At a Jewish Chautauqua convention in Atlantic City in July 1902, Rabbi J. Leonard Levy of Rodef Shalom Congregation gave a well-received address on ‘Religious Aspects of the Immigrant Problem.’ According to a report in The Pittsburgh Leader. ‘The large synagogue (then on Pennsylvania Avenue) was not only crowded, but many clung to the doors and filled the steps, bending every muscle to catch the eloquent words spoken.”

The Jews first came to Atlantic City as tourists, “because Atlantic City was all about the train,” Atlantic City real estate developer Leo B. Schoffer told the independent Jewish newspaper, The Forward. “People from the teeming inner cities – whether they were Jews or Italians or Irish or African Americans – could get on the train and escape, so Atlantic City became a prime vacation spot, with each ethnic group claiming its area of the beach or town. It wasn’t really exclusive in that sense, but you just would naturally gravitate to where people of your kind were.”

Schoffer was so fascinated by the history of Jews at the shore that he wrote a book about it titled, “A Dream, a Journey, a Community: A Nostalgic Look at Jewish Businesses in and Around Atlantic City.”

Schoffer’s parents were Holocaust survivors who originally settled in New York. “But when offered some land and the opportunity to start a chicken-and-egg business in Egg Harbor Township, Schoffer wrote, “They grabbed it.”

By the 1950s and 1960s, he said, the business was thriving. Eventually, to take advantage of Atlantic City’s tourist trade, Schoffer’s father opened the Lafayette Hotel as a kosher establishment.

“Even in the Jewish community, there was differentiation,” he said. “There would be a Romanian-Jewish restaurant and a Hungarian Jewish deli; something for everyone.”

Schoffer said that a lot of his friends came from families who visited Atlantic City on vacation and then decided to move there. There was some anti-Semitism, he admitted, but that was mostly in certain primarily high-end hotels that excluded Jewish customers. Among most full-time residents, as well as working-class tourists, he found little prejudice and lots of opportunity.

With the beginning of Atlantic City’s decline in the mid-1960s, vacationers found other places to go, and with the advent of legalized gambling, most of the Jewish businesses closed or moved. As Schoffer wrote, “Casinos and related businesses were corporate, not family based, and little today resembles the small merchants who dotted the main shopping avenues and the Boardwalk.

“I wrote the book because I realized that was a time that was fading from memory, when you would get your first suit at a Jewish-owned clothing store, go every weekend to a Jewish-owned bakery and be a pool boy in the summer at a Jewish-owned little motel.”

As for the two, best-known Jewish hotels, the property that once was Teplizky’s is now part of the Tropicana. The fate of The Breakers, the first hotel in the city to observe kosher dietary laws and long known as “The Aristocrat of Kosher Hotels,” was unfortunate. It was demolished in May of 1974, having sat vacant and deteriorating since 1965.

In honor of the long and storied Jewish presence in Atlantic City through the years, a nonprofit organization called ACBHM was formed some 15 years ago to raise funds for a Holocaust memorial. Designs were commissioned for the memorial, which would be located on the Boardwalk near Stockton University’s Atlantic City campus. Funds have been raised and the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority approved it, reserving a $500,000 matching grant for the project. The Jewish community, still quite substantial in Atlantic City, Margate, Ventnor, and Longport, looks forward to a future unveiling.

L’shanah tovah!