“Let no man (or woman) choosing the law for a calling for a moment yield to this popular belief that lawyers are necessarily dishonest. Resolve to be honest in all events…If you cannot be an honest lawyer…choose some other occupation.”

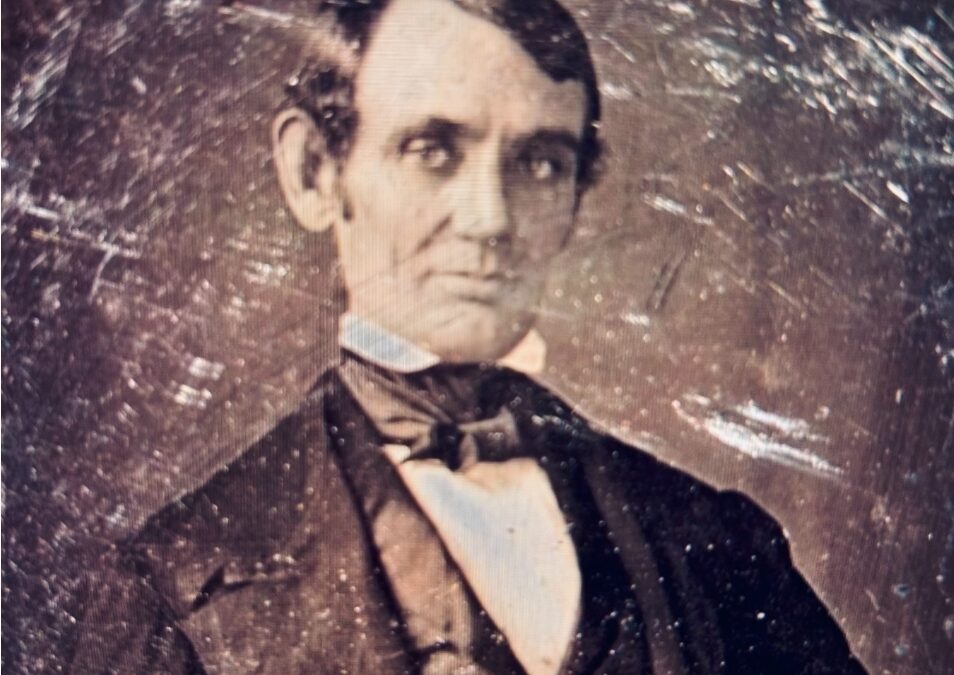

Written in 1850, this was the earnest advice Abraham Lincoln offered young lawyers in his “Notes for a Law Lecture.”

He modeled these principles during his 25-year law career, often refusing to argue cases he considered dishonest. If Lincoln believed his client was fraudulent, he would withdraw from the case.

Born in 1809 in the backwaters of Kentucky, Abraham Lincoln had less than one year of formal education, but he taught himself many disciplines by reading books. When he was 21, after being part owner of a grocery store, a surveyor and a postmaster, he moved to Springfield, Illinois.

He was ambitious – fascinated by the law and the budding judicial system of a young America. During the Black Hawk War of 1832, Lincoln met John T. Stuart, a lawyer who was so impressed by Lincoln’s brilliant intellect that he encouraged him to study law. Lincoln studied many of Stuart’s law books and a second-hand copy of “Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Law of England.”

In the early 1800s, law schools were rare west of the Mississippi River, so aspiring lawyers studied as apprentices. Lincoln studied diligently under Stuart.

In March 1837, he passed the oral exams administered by Stuart and a panel of lawyers, and was admitted into the Illinois bar. He quickly accepted a junior partnership with Stuart’s firm.

During his early years as a lawyer, Lincoln served as a rider on the Eighth Judicial Circuit, alongside fellow lawyers and a judge. Each year, during the spring and fall, these circuit riders would loop through Central Illinois, bringing the “courts” to the people, and hearing and settling legal disputes.

For Lincoln, riding the circuit provided invaluable networking opportunities. He established professional relationships with colleagues and honed his skills as a criminal and civil lawyer, building a reputation as one of the best trial lawyers in Illinois.

In 1841, Lincoln partnered with Stephen Logan, a high-powered, respected circuit court judge. Under Logan’s mentorship, Lincoln was introduced to new areas of law. He handled more complex litigation, including bankruptcy, land title, slander and cases before the Illinois Supreme Court.

As Lincoln’s reputation grew, he became known for his entertaining courtroom antics. His witty storytelling and courtroom joke-telling swayed jurors in his favor. Lincoln possessed the intellectual competence to break down complex legal jargon into everyday language. As a result, he connected with juries and won cases.

By 1844, Lincoln founded his own law firm, inviting William Herndon to join him as a junior partner. During that time, Lincoln tried and won the People v. Armstrong murder case. Using “The Old Farmer’s Almanac,” Lincoln discredited the key witness, Charles Allen, by proving that the moon was too low in the sky on the evening of the murder for Allen to have been a reliable eyewitness. The defendant, Duff Armstrong, was acquitted.

While working with Herndon, Lincoln represented major railroads, including the Illinois Central Railroad and the Alton & Sangamon Railroad. Lincoln defended these railroad giants in tax disputes and property damage cases. In 1857, Lincoln’s victory in the Effie Afton case helped expand rail transportation.

As a lawyer, Abraham Lincoln tried over 5,600 cases and worked tirelessly for justice. His love of the law fueled his dedication and passion.

In 1861, Lincoln left Springfield for the White House. Concerning the sign for his business, “Lincoln-Herndon, Attorneys at Law,” he told William Herndon, “Let the sign hang there undisturbed. I will be back to continue practicing law.”

Abraham Lincoln never practiced law in a courtroom again.