They came, they wrote, they ate

Most entertainment industry veterans agree that the 1980s and 1990s represented Atlantic City’s golden era of traditional casino entertainment. All of the legends – from Sinatra to George Burns – mostly on view only in Las Vegas before the legalization of gaming here, were booked regularly here.

The hotel/casino press/publicity offices worked differently then. Very often, when a headliner was booked for a weekend, a casino would hold a press luncheon on a weekday afternoon prior to the weekend of the shows. The star would show up, answer questions, and kibbutz a bit, with the hope that the press would write advance articles publicizing the performance.

As the writer of the Backstage entertainment column for Atlantic City Magazine, which was syndicated to several other New Jersey publications, I was always on the press corps invite list.

Most of the lunches were buffets, and our little group of Atlantic City and Philadelphia press people behaved themselves when it came to food, but there were a few exceptions. A couple of the Philadelphia-based press corps members were not bonafide journalists. They “wrote” a weekly column for a barely-read and barely-literate Philadelphia rag for one reason: to get free food.

They could always be found at the head of the buffet line. Their first order of business was to get as many shrimp as possible. That’s how the Atlantic City entertainment press corps earned its unfortunate nickname back then: “the eating press.”

The press conferences were always fun, though the stars on hand had answered many of the questions posed to them hundreds of times before. I preferred to hang back, listen to what was asked and answered, and wait around until most of the press departed. At that point, if I had what I thought was a good question to ask, I’d go up to the headliner, introduce myself and ask away.

Three press corps memories stand out.

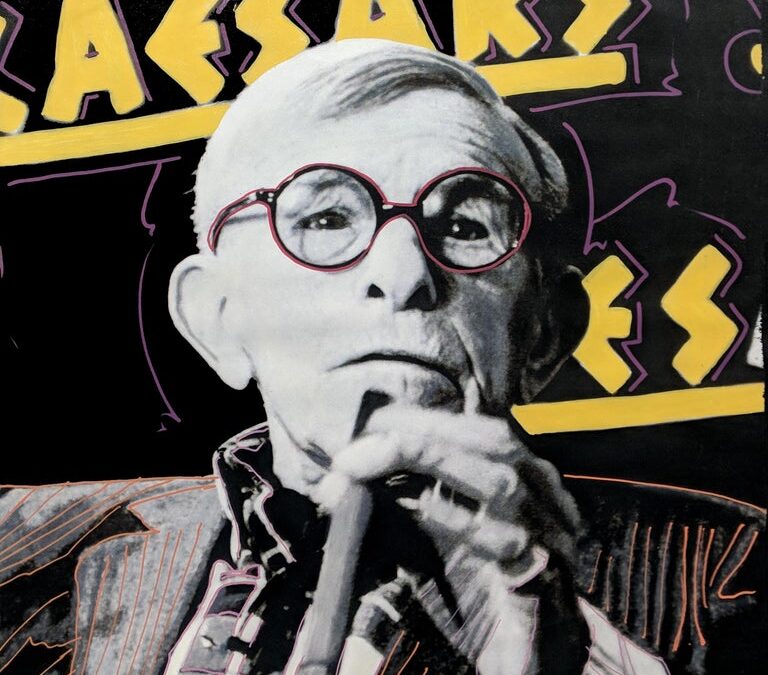

Legendary comedian George Burns signed a 15-year contract in 1981 to perform at Caesars in Atlantic City. The contract would have expired when he was 100.

Around 1986, when Burns was 90, he was booked at Caesars with his one-time protégé, Ann-Margaret, as his opening act. Margaret was not on hand, so Burns handled the press himself, fielding the standard questions about his age, etc.

After most of the press had departed, I walked up to him.

“Mr. Burns, I want to ask you something,” I said.

“What do you want to know, kid?” he asked.

“You’ve been sold out here for weeks, and you’re sold out wherever you go. So, why do you bother doing these press conferences?”

His reply: “Because, kid, it’s what we do.”

It’s a moment and a lesson I’ve never forgotten, and for a brief moment, Burns dropped the façade of a wise-cracking senior citizen. Whenever I get winded, schlepping my drums or sound system around to the next gig, I recall what George Burns said: “It’s what we do.”

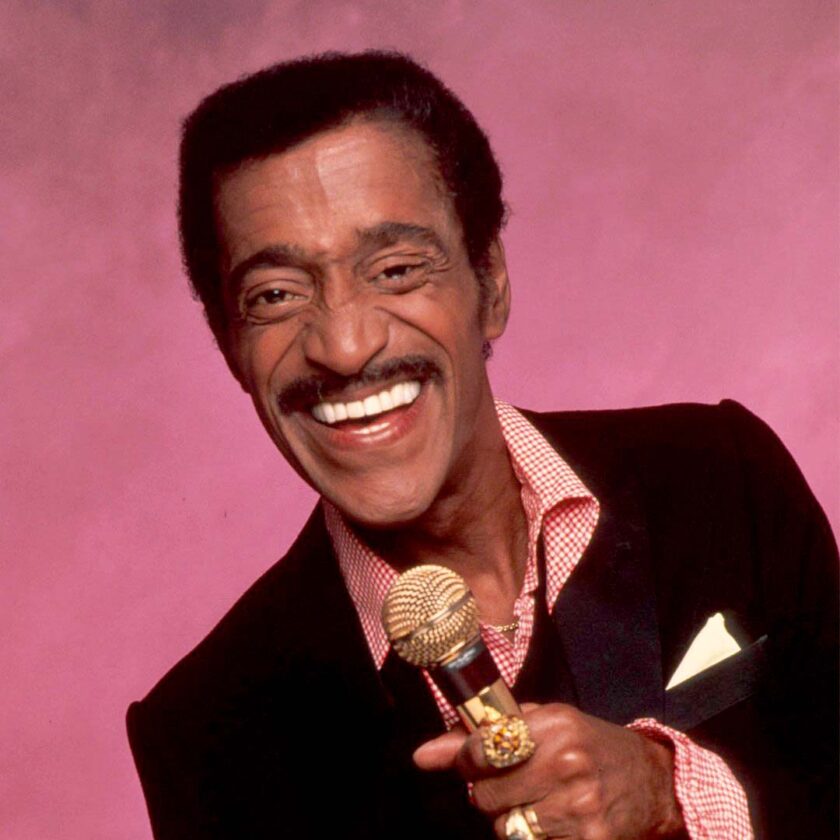

Sammy Davis Jr. had a long history in the city. He worked at Club Harlem, the 500 Club and most of the casinos. And his mother, Elvera “Baby” Sanchez, tended bar for years at Grace’s Little Belmont jazz club on Kentucky Avenue.

With the advent of casino gambling in Atlantic City, Davis was one of the first performers booked here, first at Caesars, and later, perhaps at the suggestion of his friend, Frank Sinatra, at the Golden Nugget, which became Bally’s Grand.

On the afternoon of Oct. 11, 1985, Davis gave a press conference in the Golden Nugget’s nightclub, just prior to a scheduled rehearsal. He had recently come off a hip operation, and it was clear that walking was challenging for him.

After the standard questions about the Rat Pack and his thoughts on today’s music, I stepped in.

“Mr. Davis, you were one of the great drummers. Why aren’t you playing drums in the act anymore?”

His answer made a lot of sense, though in retrospect, the reason he wasn’t playing drums in his act at that moment was likely because of the hip issue.

“Have you heard Buddy Rich lately?” he asked me.

“I’m always hearing Buddy Rich,” I replied.

“Then you know that to try to do anything he does is just impossible. Even though he’s one of my dearest friends, after hearing Buddy again and again, it just didn’t make sense to me to keep playing drums in the act.”

Davis had another hip operation in 1988, but to the best of my knowledge, after he had that first operation three years earlier, he never played drums publicly again. That was a shame. He was a good drummer.

Back in the day, when someone asked me to describe the performance of Don Rickles, I could only say, “You have to see him in person. Words can’t describe the show.”

Yes, he was an insult comic, and yes, a good part of his routine was anything but politically correct by today’s standards. But I found him to be hilarious, and so did thousands of others.

He worked at several Atlantic City casinos from 1978, when Resorts International opened as the city’s first hotel/casino, until less than a year before his death in 2017 at age 90.

I interviewed Rickles in advance of a 1979 Resorts appearance and made sure his publicist got a copy of it when it was published. During the interview he seemed surprised that I knew about fellow insult comics like Jack E. Leonard and B.S. Pully, and he remarked that he wished every interviewer had “done their homework” like I did. I let him know that I was also a working jazz musician; he remarked, “Oh…you’re in the business. Now I understand.”

At the official press conference at Resorts, I tracked him down and introduced myself. He not only said he loved what I did, but he also took me around and introduced me to almost everyone in the room, including famed press agent/publicist Lee Solters, telling one and all that “this is a kid who is going places.”

Something like that doesn’t happen often in this business of writing. But then again, with the Atlantic City Entertainment Press Corps, aka “the eating press,” anything was possible.