By Sarah Fertsch

Staff Writer

America’s first nationally protected reserve is located here in South Jersey. A closer look reveals why the New Jersey Pine Barrens is one of the most unique habitats in the world that’s well worth protecting and exploring.

Let’s jump back in time. According to the Pinelands Preservation Alliance, the Atlantic Coastal Plain began to form about 200 million years ago. Starting 100 years ago, the Atlantic Ocean repeatedly covered the coastal plain, then withdrew, leaving behind layers of geologic material in the area we know as the Pinelands.

As the Earth changed at the end of the final Ice Age 12,000 years ago, plants and animals emerged. Once the land was dry and warm, pine trees began to sprout from the soil as an evolutionary response to the harsh cold.

The Lenape people inhabited South Jersey 2,000 years later. Colonization by European nations began in the mid-1600s. The Swedes, the Dutch, and British forced out the native tribes. The Europeans harvested cedar, oak and pitch pine trees to industrialize the area, establishing shipbuilding and saw mills.

In the 1740s, charcoal and bog iron resources were developed in the Pine Barrens and the iron industry was born. Settlers built iron furnaces including the one at Batsto Village. Iron from the Pine Barrens was vital during the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 for cannons and cannonballs.

The Pine Barrens iron industry was eventually overshadowed by Pennsylvania iron, which was of higher quality and could be produced more cheaply, leaving Batsto Village and other Pine Barrens iron towns without work. Residents left in search of employment, turning these formerly bustling hubs into ghost towns. Other industries in the Pinelands like glassblowing, cranberry farming, cotton and paper milling carried on for a time but never reached scale of the iron industry.

Over the years the Pine Barrens has been associated with ghoulish mysteries, legends and folklore involving monsters. Most famously, the Jersey Devil is said to have been born the 13th child of “Mother Leeds” in 1735. Upon birth, the hideous monster spread its wings and flew away, hiding out in the Pinelands for eternity. Other folk legends like Captain Kidd and the Black Dog also have Pinelands connections.

“The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness” was the title of a 1912 book by psychologist Henry Goddard. The book documented genetic research that observed the Kallikaks, pseudonym for a family who lived in the Pinelands. The study concluded that residents of the area were biologically inferior. The study has since been debunked as biased and based on eugenics.

Other than a few early aviation crashes in the 1920s, the Pine Barrens remained mostly untouched and in obscurity moving into the 20th century. Locals kept to themselves and managed small family cranberry or blueberry farms. The area’s sandy soil deemed the land poor for farming many crops, and its earth deposits such as sand, gravel, and clay could not compare to the oil, coal, and iron of Northeastern and Western Pennsylvania.

Philadelphia urbanites called these backwoods families “pineys,” a derogatory term implying unsophistication and old-fashioned lifestyles. Even as Atlantic City and other beach towns developed along the Jersey Shore, the Pinelands was affected minimally.

Meanwhile, residents of the Pine Barrens worried that the dense forest would be destroyed and the water supply exploited to accommodate expansion of the Philadelphia suburbs. The low cost of land in the pines tempted developers, and plans for a new international airport were laid to use the land within Wharton State Forest.

In the 1960s, the political climate favored liberal causes like protections for healthcare, seniors, labor rights, and land preservation.

New Jersey Republican Rep. Edwin Forsythe proposed that 1.1 million acres of a unique forest in South Jersey be nationally protected. Ultimately, the Pinelands National Reserve became the first nationally protected lands through the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978.

The reserve contains Wharton State Forest, Byrne State Park, Batsto Historic Village, Bass River State Forest, and Penn State Forest. The area was designated a U.S. Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1983 and an International Biosphere Reserve in 1988.

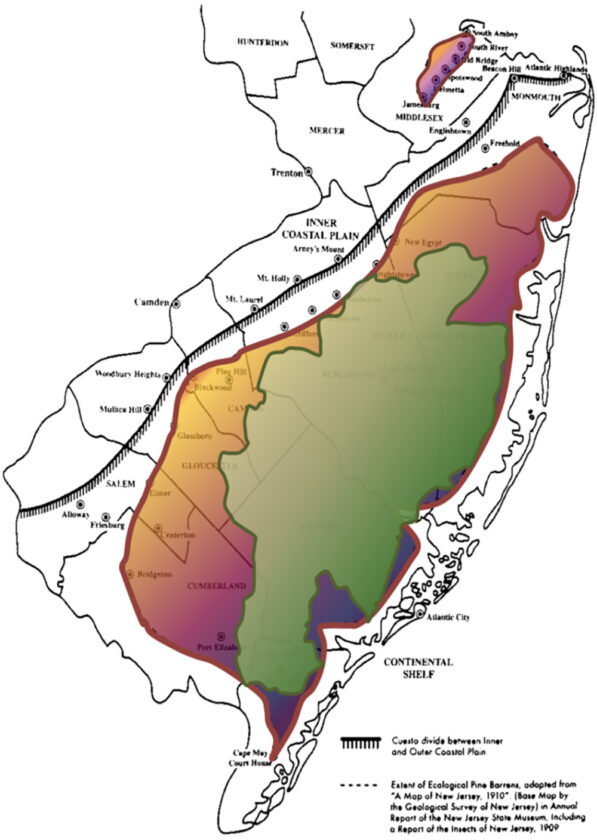

According to the New Jersey government website, the Pinelands National Reserve spans seven counties and covers 22 percent of land in the entire state. It is also the largest body of open space in the Mid-Atlantic region between Boston and Richmond.

So why are the Pinelands worth preserving? Well, protecting the regional water supply is one reason. It’s home to the Kirkwood-Cohansey aquifer, a 17 trillion-gallon underground water supply that serves all of South Jersey.

It’s also habitat to dozens of rare plants and animals, attracting hundreds of biologists worldwide. Of the almost 40 native species, explorers may stumble upon a beaver, rattlesnakes, barred owl, snapping turtle, eastern ribbon snake, wild turkey, and screech owl.

One of the rarest creatures of the Pinelands is the Pine Barrens tree frog, which has become even more rare due to habitat loss. The amphibian is most commonly found in South Jersey, but also exists in North and South Carolina as well as Alabama. In 1983, Andy Warhol created a print series based on the species to raise awareness of the need for environmental protection.

The Pinelands Preservation Alliance reports that the reserve is home to eight species of gymnosperms (plants like the pine trees that do not produce true flowers), 800 species of flowering plants (angiosperms), 25 species of ferns, 274 mosses, and at least 100 (but probably 300-400) species of fungi.

The pitch pine is the most common and characteristic organism of the Pine Barrens, occupying more than 700,000 acres of New Jersey. These trees are known for their thick, resinous bark and deep roots, which allow them to thrive in drought conditions or parasitic infestations. The pine needles from these trees are the main food source for rabbits, mice, and birds that co-habitate in this ecosystem.

Pitch pines have an incredible quality that excites scientists and tree-lovers across the planet: they can grow new branches from their trunks and even their roots. Their thick bark protects them from most forest fires, so they can regenerate after almost all fire damage. After the Wharton Forest fire in June, many observed burnt-black trees sprouting little green growths from the ashes.

Also, the pine cones of this species are opened through extreme heat, ensuring new life in a forest decimated by fire. This evolutionary adaptation allows pitch pines to compete against oaks, whose acorns typically allow the tree family to grow quickly and easily.

In a fire (which is fed through the hundreds of needles on the forest floor), pitch pines will win out. Overall, pines beat oaks by taking in more sunlight, utilizing more water, and absorbing more minerals.

Beneath the iconic pitch pines, rare flowers blossom along the forest’s understory. The Pine barrens gentian, bog asphodel, swamp pink, and dozens of variations of orchids survive exclusively in the Pinelands.

Most astonishingly, carnivorous plants have taken over the Pine Barrens. Sundews, bladderworts, and pitcher plants have developed behaviors to entice creatures and then swallow them up. Pitcher plants release aromas that tempt insects. When they land on the plant, they are trapped. Bladderworts, as their name implies, have tiny sacs embedded in the soil near their roots and suck up small bugs to immediately digest.

The ecosystem is marked by its low acidity and low-nutrient water and soil. Like the northern forests of Maine and the Everglades of Florida, the Pinelands make New Jersey distinct and wild. Locals and tourists can enjoy camping, hiking, kayaking and searching for the Jersey Devil. Most importantly, locals, particularly in South Jersey, enjoy the clean air, clean water, and beautiful scenery that comes with celebrating the Pine Barrens as our home and neighborhood.

Sarah Fertsch was born and raised in Egg Harbor Township, and holds a dual degree in public relations and political science. Prior to joining Shore Local full-time, she worked at a CSPAN affiliate, writing about Pennsylvania legislation. When she isn’t writing, Sarah enjoys painting, horseback riding, and Crossfit.