Remember when

with Chuck Darrow

In Atlantic City’s 150-plus-year history, one would be hard-pressed to conjure a more dramatic, impactful week than that which began on Aug. 24, 1964.

That was the first day of the 1964 Democratic National Convention, which was held at what was then Atlantic City Convention Hall (now James Whalen Boardwalk Hall). Because then-President Lyndon Johnson was a mortal lock to win re-nomination, the hundreds of media types who descended on the town had little in the way of real “news” to cover. Instead, they spent the ensuing four days putting the final nails in the coffin of AC tourism, telling millions of people around the world about the overpriced, understaffed, beat up, un-air conditioned rattraps in which they were bivouacked.

The resulting awful publicity ultimately set in motion the wheels of the legal-casino movement, which culminated in the opening of what was then Resorts International (now Resorts Casino-Hotel) in 1978.

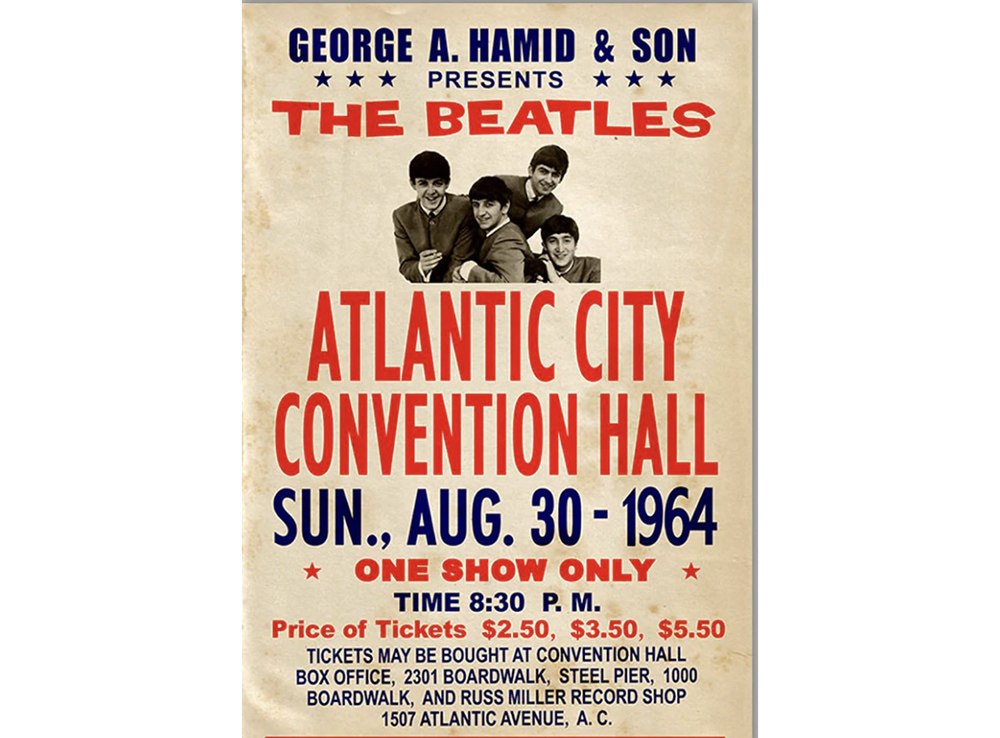

But just a few days after the convention concluded, another event of epic proportions took place in the same building: On Aug. 30, The Beatles played Convention Hall as part of their epochal first U.S. tour.

During a recent phone chat, legendary Philadelphia TV news anchor Larry Kane, who, as a 21-year-old reporter for a Miami radio station, spent that summer on tour with the Fab Four, remembered the local stop of that epic road trip in vivid detail.

Drama en route

According to Kane, who today contributes political analysis to Philly’s KYW-FM (103.9), the AC visit, which took place Aug. 29 and 30, began on a inauspicious note: The tour bus stopped at a rest stop on the way to Atlantic City from New York City, and as Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield of The Righteous Brothers tossed a football, Medley informed Kane that the act was leaving the tour.

“They quit. They couldn’t stand the fact the audience didn’t want to hear them,” said Kane, referring to the mostly female fans who were only concerned with seeing the Mop Tops.

Arriving in AC, continued Kane, the touring party checked into what he recalled only as “an old, old hotel.

“The second night, the night of the concert, they transferred us to the Lafayette Motor Inn [located between Pacific Avenue and what was then Chalfont-Haddon Hall Hotel and is now Resorts]. We went over to the Lafayette in the daytime; they brought us over under the Boardwalk.”

Passing time

Once ensconced on North Carolina Avenue, John, Paul, George and Ringo whiled away the hours while virtual prisoners in the hotel.

“One of them wanted to go on a rolling chair, but they couldn’t get out of the hotel [for fear they’d be in physical danger],” offered Kane. “They also wanted to go in the ocean. They told me in Philadelphia [the next stop on the tour] that they could see the ocean, and they thought it would be wonderful to go in it. But the only time they got out was when they went to White House Subs.”

Kane noted there was one thing in particular that absolutely jazzed the lads from Liverpool. “The thing that they really loved was that they were in the town whose streets were used in ‘Monopoly.’ Ringo said to me, ‘Where’s the Short Line [railroad]?’ I said, ‘I don’t think there is one.’”

Kane added The Beatles conducted the game with a twist.

“They played ‘Monopoly’ for real money. We’re sitting on the floor—George, Ringo, [singer-songwriter-tour-opening-act] Jackie DeShannon. They asked me to play and I said, ‘I can’t afford to play for real money.’ They said, ‘We’ll give you money to play. If you win, we’re gonna take it back. If you lose, you don’t have to pay.’ I didn’t do very well.”

Trouble at the hall

Kane described the scene around Convention Hall as “really chaotic.

“Out of all the concerts, this was the most raucous. Because of the nature of Atlantic City–you have the Boardwalk, you have the streets—there were people everywhere. They were under the Boardwalk, they were on top of the Boardwalk. It was just insane.”

Getting the band from the hotel to the hall was harrowing. Kane provided a copy of an interview he taped with Derek Taylor, the Beatles chief publicist, the day after the AyCee show. In it, Taylor described a scene that could have easily ended in tragedy (the “Leffler” he mentions was part of the band’s entourage); “Bess” was another publicist:

In the car in front as usual, were the four Beatles and their road manager, Neil Aspinal, who knows more about getting in and out of hotels and theaters than anybody alive, having been with the Beatles since the very beginning. Their car drew up outside the convention hall and was immediately surrounded by kids. How it happened, I don’t know, because everybody had been warned that Beatle crowds were unpredictable and wild and dangerous.

Neil, as usual, guided the driver to what to do, whether to move on a bit or to stop. Still, the police bashed their way through. I’ve never seen movement like it. They just had to crash through to protect the crowds from themselves.

One man at least, who as far as I could see, had been climbing across the [hood], had his leg either broken or very badly bruised, and it really was an indescribable sight.

And then the police managed to clear a way for the Beatles to open the [car] door. [But it] then closed again because it became unsafe. And Leffler ordered everybody out of our car to go and help. Unfortunately, this meant that Bess was to stay behind; of course, the kids got into the car and got at Bess and she had to get out as well.

So there we all were separated from the Beatles by the crowd and ourselves in danger of being battered by the police. [We] are not blaming the police because they did have an incredibly difficult job to do, and they had to protect the lives of the Beatles, which were endangered.

Kane didn’t have much to say about The Beatles’ performance that night, other than that the auditorium’s horrible acoustics and primitive sound system made for an aural nightmare. But as it turned out, for Kane, the most memorable parts of the evening came after the show.

“We got back to the hotel and they called a few of us and said, ‘Come up to the roof.’ It was a very elegant penthouse. They had all kinds of food there: They had cheesesteaks, pizza. I’d say there were 15 or 20 of us there [including] The Beatles, [band manager Brian Epstein] and Taylor.

“So there we are in this nice, air-conditioned penthouse and this guy walks in with this gigantic…crate. He opened it up and inside was a 35-millimeter projector. I couldn’t believe it. They put up a screen, and he surprised us by showing ‘A Hard Day’s Night.’

“To me, the best part of it was they didn’t like how they looked [onscreen].”

Kane admitted that another part of the evening’s festivities wasn’t quite as wholesome.

“A guy walked in with 10 or 12 young-looking women–I would say they were extremely attractive–and said, ‘Gentlemen, take your pick.’ I was naive. I did not know they were hookers.”

He made it a point to add that when he realized who the women were and why they were there, he declined to avail himself of their particular services because he sensed it would violate journalistic ethics.

Thus the Beatles’ only visit to Atlantic City ended. The next day, they were loaded into a fish-delivery truck to avoid detection by fans and driven to Philadelphia– a fittingly bizarre ending to a most epic week in AC history.

Remembering When is a monthly column that looks at Atlantic City’s often-wild, always-fascinating history.