By Bruce Klauber

Contrary to the widely-held belief, Louis Prima did not invent the concept of the Las Vegas lounge act. That honor belongs to guitarist/vocalist Mary Kaye.

Kaye and her trio were a wildly entertaining unit that virtually created the lounge phenomena around 1953 at Vegas’ Last Frontier Hotel and Casino. Whether by choice or by chance, Kaye and the gang created the free-wheeling, all-night party atmosphere where anything could and did happen.

Before Kaye, Vegas casino lounges were simply a place where gamblers could have a drink and rest a bit before returning to the tables. Not long after Kaye, casinos realized that bringing talent into the lounges could not only be a money-maker, but could also serve as another reason a Vegas visitor would visit one casino instead of another. In other words, the idea became, “Hey! Look who’s playing in the lounge!”

Enter trumpeter/singer/entertainer Louis Prima.

Prima had been a big name in the late 1930s with a superior Dixieland outfit, Louis Prima and his New Orleans Gang, and was able to parlay that notoriety to become leader of a successful big band.

Prima had been a big name in the late 1930s with a superior Dixieland outfit, Louis Prima and his New Orleans Gang, and was able to parlay that notoriety to become leader of a successful big band.

The band, which lasted from 1941 through 1951, was gigantic. Focused on Louis’ singing, clowning, and his Italian novelty songs such as “Please No Squeeza Da Banana,” “Baciagaloop (Make Love on the Stoop),” and “Felicia No Capicia,” sold thousands of records.

Prima’s band brought in an astounding $440,000 for a six-week stand at The Strand in New York City, and commanded as much as $38,000 for an afternoon performance.

During its years of success, the band appeared often on Atlantic City’s Steel Pier. The Pier’s George Hamid, who had a soft spot for entertainers who were having career issues, booked the Prima ensemble as late as 1953, when Prima’s career had bottomed out. By then, big swing bands were long out of fashion.

Prima continued to lose big at the track, and he was paying alimony to several ex-wives.

In 1951 in Virginia Beach, he “discovered” a young singer, barely 20 years old named Keely Smith. Louis and Keely traveled around the country, picking up local musicians to accompany them in every town they worked, in hopes of recapturing the old magic. As Keely said many years later, “Man, we worked in some god-awful places!”

In 1954, Louis and Keely snagged a booking in the lounge at the Sahara in Las Vegas. Years before, Prima headlined in the main showroom. That’s how far his star had fallen. According to Keely, “The band was good, and musicians were fine, but nothing was really happening.”

The something that was missing turned out to be saxophonist Sam Butera. Prima was told about Sam and his band, how electric and on fire the group was, and how they were knocking them dead in New Orleans with their mixture of jazz, rhythm and blues and rock and roll. He was so excited about what he was told about Butera that he summoned Sam and the band to the Sahara. “On Christmas Day,” as Sam once told me.

After a few days in Vegas with Louis, Keely, Sam, and Sam’s band – The Witnesses – the act just caught fire, and it wasn’t long before the lounge at the Sahara became the place for everyone to go, including the biggest celebs in Vegas.

By 1956, the ensemble was one of the hottest acts in the country. Keely’s deadpan act played beautifully against Louis’ wild clowning and the romping and stomping swing of Sam Butera. Make no mistake about it: Musically, Sam Butera was the architect of the Louis Prima sound, beautifully combining elements of New Orleans jazz, Prima’s jiving Italian novelties, swing, and rhythm and blues – all backed with a percussive shuffle beat that wouldn’t quit.

By 1956, the ensemble was one of the hottest acts in the country. Keely’s deadpan act played beautifully against Louis’ wild clowning and the romping and stomping swing of Sam Butera. Make no mistake about it: Musically, Sam Butera was the architect of the Louis Prima sound, beautifully combining elements of New Orleans jazz, Prima’s jiving Italian novelties, swing, and rhythm and blues – all backed with a percussive shuffle beat that wouldn’t quit.

After Louis and Keely divorced around 1961 Prima, with Sam Butera and The Witnesses in tow, continued with some degree of success, but it was never the same.

In 1975 Louis Prima was diagnosed with a brain tumor and lapsed into a coma. He was in that coma for three years before he passed at the age of 67 on Aug. 24, 1978. That was three months after the first casino opened in Atlantic City. Had Louis lived, he would have been a giant here.

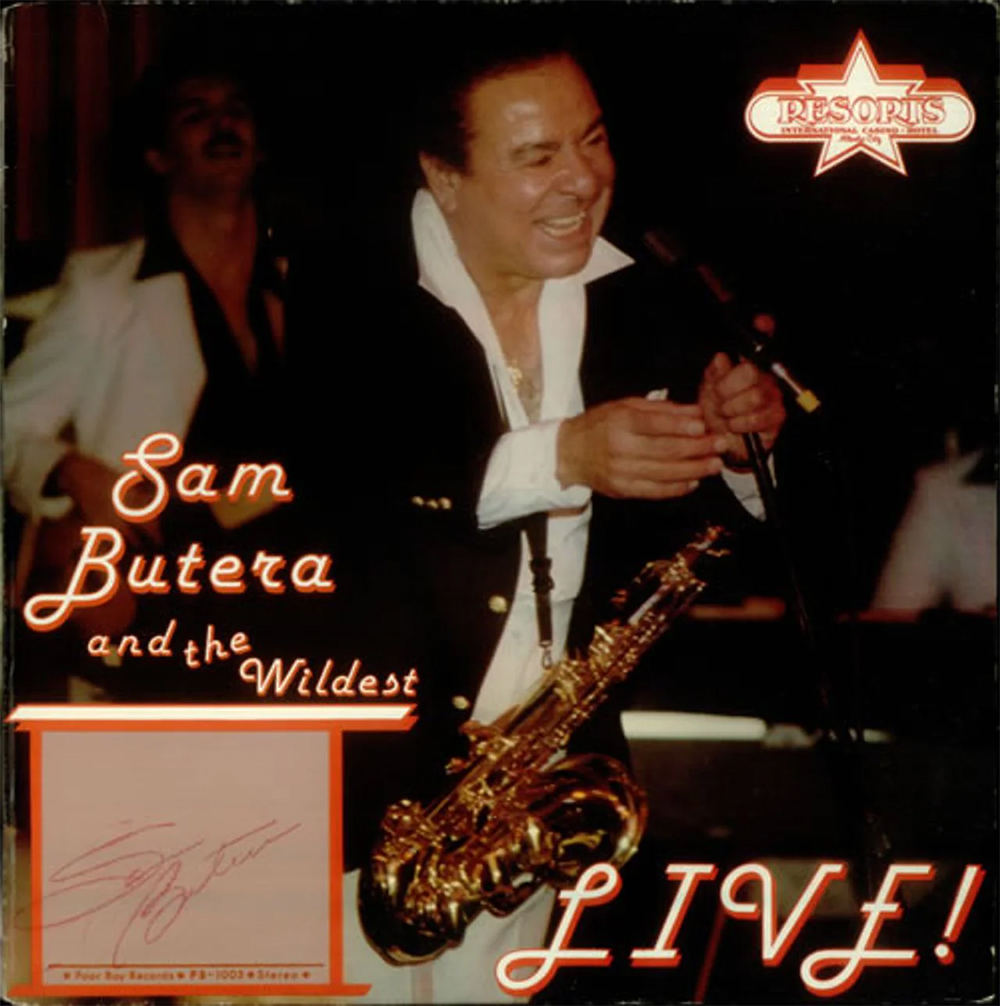

When Louis became ill, Sam Butera continued on his own, but still felt he needed a female singer out front with him. He first paired with Louis’ last wife, singer Gia Maione, but that didn’t work out. Even though it seemed to be a dynamite act, Keely Smith with Sam Butera and The Witnesses, didn’t last either.

Sam, after watching and admiring what Louis did on stage every night for 20 years, had the spirit of Louis within him, and coupled with his virtuoso sax playing, Prima-like vocals, and a crack back-up band of Vegas’ best.

When Resorts International opened in Atlantic City, the talent buyers had to book headliners for the main stage, and had to come up with several lounge acts to appear in Resorts’ Rendezvous Lounge. The buyers’ only frame of reference was Las Vegas, hence the booking of Butera, along with other Vegas stalwarts: The Treniers and Freddie Bell and The Bellboys, into the lounge.

Anyone who was there during the time Butera was in residence at the lounge will talk about unforgettable evenings of sheer energy as well as the “anything can happen” atmosphere that Mary Kaye’s Trio pioneered over two decades before.

Headliners finishing their stints at Resorts’ Superstar Theatre, including Frank Sinatra, would almost always stop in the Rendezvous to see and/or kibitz on stage with Sam Butera and the group he now called “The Wildest.” All kinds of things went on in that lounge, and during my time as columnist for Atlantic City Magazine, I was able to report on one of them.

Comedian Alan King, who had been headlining at the Superstar Theatre, wandered in the Rendezvous Lounge to dig Sam and the guys. He came in alone and grabbed a seat at the bar, sitting next to me. Seems my name was familiar to him in that my first book on jazz legend Gene Krupa had been published recently.

What I didn’t know, and what Alan King told me, was that he was not only a major jazz fan, but first got into the business as a bouncer and a doorman on that hotbed of jazz, New York City’s 52nd Street.

I was beyond fascinated as he told me stories of how he knew Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk and the rest of the innovative be-boppers on “The Street,” and how much he dug their music. Then he told me he was going to go up on the stage and “sit in” with Sam and The Wildest.

“And what the heck are you planning on doing up there?” I asked. “Watch and learn,” he replied with a grin.

The next thing I knew, comic Alan King was up there scat-singing, ala Mel Torme’ and Ella Fitzgerald, and doing one hell of a job of it. He was swinging and kept up with every riff Sam Butera laid on him.

He finally made it back to his seat at the bar after much applause. I told him how much he was swinging and that I couldn’t believe what I heard. His reply? “Write about that, kid.”

Alan and Sam, I just did.

Bruce Klauber is the biographer of jazz legends Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich in books and Warner Brothers films, a contributor to Down Beat magazine and other music journals, and served as technical advisor on the Oscar-winning film, “Whiplash.”

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and a working jazz drummer and vocalist since childhood. He served as Technical Adviser on the Oscar-winning film, “Whiplash,” and on the 2018 Mickey Rourke film, “Tiger.” He has been honored by Combs College of Music and Drexel University for his “contributions to music journalism and jazz performance.”