By Bruce Klauber

Musically, the year 1950 was noteworthy for artists like Red Foley, Frankie Laine, Patti Page, Teresa Brewer, The Ames Brothers and Perry Como.

Among the biggest hits of that year were now-forgettable novelties such as Frankie Laine’s “Mule Train,” Como’s “Hoop-Dee-Doo,” Brewer’s “Music, Music, Music;” and The Ames Brothers’ “Rag Mop.” Conspicuously missing from the pop charts of 1950 was Frank Sinatra.

It was not a great year personally or professionally for an artist who was among the most wildly popular in music history just a few years before. His movies were no longer hits. The press was in an uproar over his courting of Ava Gardner. His CBS television show, broadcast opposite the gigantic “Texaco Star Theater” starring Milton Berle, was going nowhere and his stint on radio’s “Your Hit Parade” had ended a year earlier. Personal appearances were sparsely attended, and most significantly, his Columbia records were no longer selling.

Stylistically, his plaintive crooning was no longer in vogue as the once fashionable bobby soxers, a substantial part of his audience in the 1940s, had grown up. And record producers like Columbia’s Mitch Miller were spoon-feeding the American public ridiculous novelties like “Come-On-A-My-House” and “How Much is That Doggie in the Window?” Miller tried to foist this nonsense on Sinatra and Sinatra gamely tried. But his heart just wasn’t in it and the record-buying public knew it.

Vocally, he was maturing, but his record company producers were not maturing along with him. It was messy and it was sad, as the artist who had been on top of the world was now caught in some kind of stylistic time warp.

As bad as 1950 may have been, the seeds of a career upswing – musically, anyway – were planted in that year with the release of “Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra.” The LP was a departure from the ballads Sinatra had been known for. With orchestrations by big band veteran George Siravo, the eight songs within were light swingers such as “It All Depends on You,” “Lover,” and “My Blue Heaven.” It wasn’t a big seller, but in terms of music history, it was the first indicator of where Sinatra was headed musically.

Though his career may have been heading downward, Sinatra still had his supporters and his fans. Two of those fans, Paul “Skinny” D’Amato and George Hamid, lived and worked in Atlantic City.

In a town known for its colorful characters, D’Amato was an icon. Alleged to have ties to organized crime, he owned The 500 Club – the notorious nightclub at 6 Missouri Ave., since 1942 when he and partner Irvin Wolf purchased it from Phillip Barr. Barr had been using the venue as a horse betting parlor during the day and a nightclub during the evening. D’Amato and Wolf turned it into a bonafide nightspot, open from 5 p.m. until 10 a.m. It was not a secret that until the early 1950s, it had roulette wheels, craps tables, baccarat and high-stakes card games in the rear of the club. Some say there was more gambling in Atlantic City than what arrived with legalization in 1978.

But what put the club on the map, and what enabled The 500 Club to attract top talent, was the breakthrough appearance of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis in 1946. Although the story has many versions, what is agreed upon is that Jerry was booked at The 500 Club as a single and was bombing. And Jerry knew it. As a rescue measure, he suggested the club add singer Dean Martin to the bill; Jerry had recently come to know Dean in New York, with the promise that the two of them on stage together would be dynamite.

Despite Jerry’s claim that he wrote their entire act on a paper bag during a break, the truth is that their first performance was completely ad-libbed. The basis of the act, which stayed pretty much the same for the 10 years that they worked together, was how the wild and crazy Jerry would interrupt the straight crooning of Dean. Whatever they did, it was an instant hit. Word spread quickly. The club was mobbed throughout the summer, and the venue itself was now the go-to nightspot in Atlantic City.

Although Sinatra was only casually acquainted with Dean Martin in those days, he was friends with Skinny D’Amato. And reports are that when Sinatra’s career began to go south, Skinny lent a helping hand. Sinatra’s 1948 appearance at The 500 Club was barely reported. Sinatra, of course, made one of the most remarkable comebacks in show business history, and again became a major star by the mid-1950s. He won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in 1954 for his role in “From Here to Eternity.”

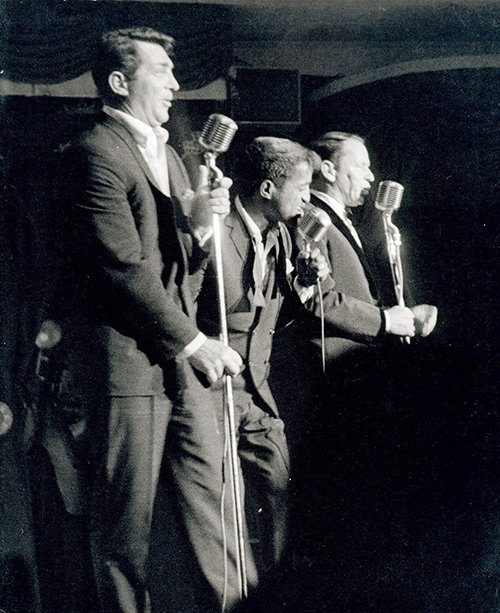

By the late 1950s, Skinny D’Amato and his club were having financial problems and Sinatra helped out his dear friend by way of now legendary performances in July of 1959, July of 1960, and an August of 1962 stint, recorded for posterity, where he was joined by Dean Martin and Sammy Davis, Jr. He was a major movie star and a bestselling recording artist. He no longer needed The 500 Club. But he was there for Skinny and he was there for Atlantic City. If you were in Atlantic City in 1950, pre-comeback, you wouldn’t have known that Sinatra’s career had hit close to bottom.

Enter Sinatra’s other Atlantic City benefactor, Steel Pier owner George Hamid. Sinatra had not appeared at the Steel Pier since he played there in 1939, when he was a boy singer with Harry James’ newly formed band. But Hamid was a Sinatra fan through and through and couldn’t have cared less about what people were saying about Sinatra’s career.

He took a major chance and booked the singer on Labor Day weekend, 1950. Hamid could have booked anyone. It paid off. An estimated 40,000 Frank Sinatra fans showed up. In an interview he did with broadcaster Ben Heller at the Pier on WMID Radio, it’s quite clear that Sinatra was in excellent spirits.

After his 500 Club appearances in 1964, Sinatra would not appear in Atlantic City until October of 1978, when he performed a concert at Convention Hall to raise funds for the Atlantic City Medical Center. He went on to play Resorts, the original Golden Nugget on the Boardwalk, and did his final shows in 1994 at the Sands Hotel and Casino.

It’s been said that Frank Sinatra had a lifelong love affair with Atlantic City. Though in later years he continued to appear in Atlantic City at Resorts, the Golden Nugget, and the Sands, nothing demonstrated the love that Atlantic City had for Frank Sinatra better than that Labor Day Weekend at the Steel Pier. Just ask one of the 40,000 people who were there.